- May 13, 2019

- David Everett

The Senior Cycle

From Grandma Bikes to Pedaling Clubs, Bikes are Obvious Option for Dutch Seniors

Being Dutch, Luitzen Dijkstra didn’t have to look far to find the activity he needed in retirement. After a heart attack, he especially wanted something to maintain his health and to increase life-giving interaction with others. In fact, Dijkstra, 62, probably could spot his eventual solution by glancing outside any time day or evening, just about anywhere in his country: bikes.

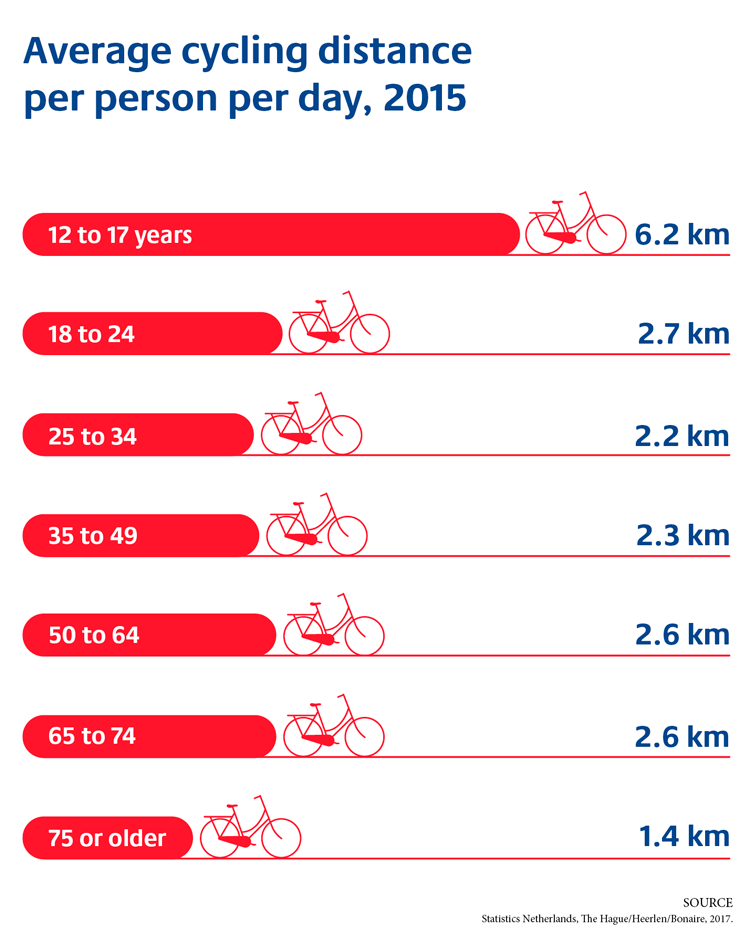

Bicycles are indeed everywhere in the Netherlands. The country famously features more bikes than people (23 million, compared to 17 million), with an average bike journey of 1.5 miles per day per person. People of all ages use them for everything from commuting to chores, but bikes have become increasingly popular for older Dutch citizens as a social foundation.

Dijkstra, for instance, is a bike trainer who helps operate a club sponsoring group rides for various ages from “eight to eighty,” as he likes to say: “The socializing aspect is the main thing — being away together, visiting surroundings, having coffee. On a bike, we also can talk together as we ride.”

In Holland, some cities and towns see fewer gas-spewing vehicles than bikes, which often offer their own, separate lanes, traffic controls, and parking structures. Watching the measured, harmonized, and organized flow of thousands of Dutch riding to and from work is a revelation of how deeply bikes have become embedded into this small, flat nation’s psyche.

In Amsterdam, the easiest way to get from point A to point B is by bicycle. On average, an Amsterdammer bikes 900 kilometers (560 miles) a year.

The benefits to older Dutch are more than you might realize, with physical health only the beginning. Cycling in Holland is studied by psychologists and sociologists as well as doctors. Studies show cycling adds to the lives of those over 60. Because of bikes, deaths from vehicle accidents are lower in the Netherlands, as is the health impact of vehicle pollution. Not only does cycling help Dutch people live an average of six months more than a typical European, but more than half of the total life expectancy increase benefits those over the age of 65. Cycling also contributes to brain health overall because of the multitasking involved in a simple ride to a café, being outdoors with others rather than sitting alone, even the complex level of trust required when you join hundreds of others in long, constantly moving lines of cyclists.

Dijkstra coaches and trains with his bike club in Peize, a smaller town near Groningen, a university city where a parking structure for 10,000 bikes was found to be lacking and where more than 60 percent of all trips occur on bikes.

“The cycling culture we have today is the outcome of a long, long, social struggle of fifty years in which the streets were conquered back from cars, inch by inch,” says Oldenziel.

Groningen was like most cities worldwide in the 1950s and 1960s – cars were increasingly taking over. But local politicians fought to support cycling, and today, bikes are favored over cars. In fact, if you want to visit the inner city, you must take public transit, walk, or pedal. Cars are increasingly restricted. The historical central marketplace — once a massive vehicle parking lot — is now a thriving marketplace again where most customers arrive on twos — feet or spoked wheels.

Another example is Utrecht, a fast-growing city in the center of the Netherlands that is building the world’s largest bike garage to match its 250 miles of dedicated bike lanes. Many in the city use a special app to locate the closest bike parking spot.

Ruth Oldenziel, an internationally known professor of technology at Eindhoven University of Technology and at the University of Amsterdam, touts Holland’s biking benefits to others worldwide. Research from her team and others show several factors merged to support the pervasive Dutch bike culture: The close-knit nation did not develop as many far-out suburbs, the image of cycling has remained positive among all ages and economic groups, mass transit is available to pair with bikes or to replace cars, and the biking infrastructure is strong and growing — all promoted by decades of advocacy for bicycles.

“The cycling culture we have today is the outcome of a long, long, social struggle of fifty years in which the streets were conquered back from cars, inch by inch,” says Oldenziel.

Cyclists of all ages use their bikes daily.

This is not to mention that gasoline prices in the Netherlands are among the highest in Europe — from $6 to even $7 a gallon. Biking can be a cheaper alternative than cars, especially for seniors on a fixed income. Bike riding becomes more leisure-focused after age 50, especially after retirement, Oldenziel says, but bicycles don’t drop in popularity among older Dutch residents until age 75.

In Holland, residents from an early age through college see no reason to add those two extra wheels. Bikes are used to get places, and nearly everyone uses them. People live closer together, and trains or other mass transit are usually available for longer trips. Some residents do not even own cars. At age 60, for instance, Professor Oldenziel is a bike-train-bike commuter. She keeps one bicycle at home for the seven-minute ride to her local train station, then another bike in the city, where she pedals a few minutes to her office. She arrives with students, janitors, clerks, and other professors; no real class distinction exists for bikes. Many Dutch riders pride themselves on having cheap or beat-up bikes.

Bikes are ingrained into Dutch culture in the same ways cars are central to the transportation culture of other countries. In the Netherlands, bikes are simply a two-wheel, self-propelled vehicle that you leisurely pedal to almost anywhere, any time of year. Weather? Dutch bike lanes are often heated and plowed in winter. Car-bike wrecks? Not so much in Holland, where cyclists enjoy their own traffic signals that stop gas-spewers to let them pass. Need to take someone somewhere? Have ‘em hop on your sturdy luggage rack. And kids? They pile into Mom or Dad’s front bike trailer or even perch on the handlebars.

Two types of bikes reflect how seniors help personify Dutch cycling culture. One is the amazingly popular omafiets, or grandma bike. People of all ages embrace this retro-style bike, which looks like something from the 1940s but is popular for its essential Dutch practicality and simplicity. The oma bike is a traditional bike with a low cross bar, sit-up-straight design, and both fenders and chain guards to make riding easy with regular clothing. Yes, you often see grandmas and grandpas on oma bikes.

The other craze is the e-bike, or electric bicycle, where a small electric motor boosts pedal power for longer rides or even the gentle hills sometimes encountered. E-bikes, in fact, have extended the cycling lives of older Dutch residents, according to Oldenziel and Dijkstra, the retiree and bike club enthusiast.

Yet the slightly increased speed and range that comes from electric bikes has, for the first time, revealed a slight warning for older Dutch pedalists: In 2017, the number of Dutch cycling deaths increased slightly, and all of the increase was attributed to men over age 65 on e-bikes, which are heavier and sometimes more difficult to control at higher speeds.

Despite this trend, cycling still is conspicuously safe in Holland on per-mile, per-capita use. Groups and clubs like those Dijkstra helps run are growing nationwide. One is a foundation called Fietsmaatjes that pairs senior riders to those with disabilities. The group focuses on two-person bikes with electric boosters that allow the riders to sit next to each other – not one behind the other like a traditional bicycle built for two. This promotes the interaction that bicycles have come to represent for many Dutch seniors, whether part of a foundation, touring club, or just pedaling to meeting a friend.

“Sometimes I think I cannot exist without my bike,” says Dijkstra. “My bike is part of my life.” ◆