- June 04, 2019

- Lauren Hassani

Going Dutch

Aging in the Netherlands

AMSTERDAM — Even a terrible skiing accident couldn’t keep Barbara Ederveen-Winkler confined to her apartment for very long. After months of agonizing rehabilitation for her broken leg, she was eager to regain some semblance of independence and mobility. On an uncharacteristically sweltering day in Amsterdam, she headed out for a jaunt around the neighborhood — not on her trusty bicycle, which she has owned for 20 years and which, pre-accident, took her on daily errands across the city, but in a wheelchair pushed by her husband, Walter.

Her experience at 68 years old has given her a glimpse into the not-so-distant future, in which she will be increasingly reliant on good healthcare providers, a network of friends and family, and easy access to all the necessities of life. In short, she has been forced to come to terms with what it means to grow old in the Netherlands, a tiny country in the midst of large demographic and societal shifts.

On this particular afternoon, Ederveen-Winkler is thrilled to be able to get outside, to eat an ice cream cone in Oosterpark, the sprawling green park just half a mile from her home, and to meander through the crowded outdoor Dappermarkt, where vendors sell everything from fresh cheese to household goods.

Slim and athletic, with salt-and-pepper hair and a ready smile, Ederveen-Winkler has the look of someone not used to sitting still. She has lived in Amsterdam for more than four decades, and in her current apartment since 1991. She chose the neighborhood for its central location and accessibility, even selecting a ground floor location for its long-term practicality — an impressive detail for a 40-year-old to consider.

Visiting their favorite cheesemonger at the Dappermarkt.

In a very Dutch way, she applied foresight and a healthy dose of pragmatism to planning for old age. The purchase of her home was part of that planning, and when she retired in 2015 after a lengthy career as a social worker, she made sure her finances were in order to carry her through the next twenty to thirty years.

In many regards, Ederveen-Winkler embodies the story of aging in the Netherlands. She is a member of the so-called “baby boom” generation, born between 1946 and 1955, that has transformed Dutch society (the post-WWII birthrate in the Netherlands was the highest in Western Europe). She reached retirement age and is growing old at a pivotal moment, as the country tries — through government programs, technological and scientific innovations, new models of care, and community-based efforts — to address the long-term sustainability of their welfare state and a ballooning population of seniors.

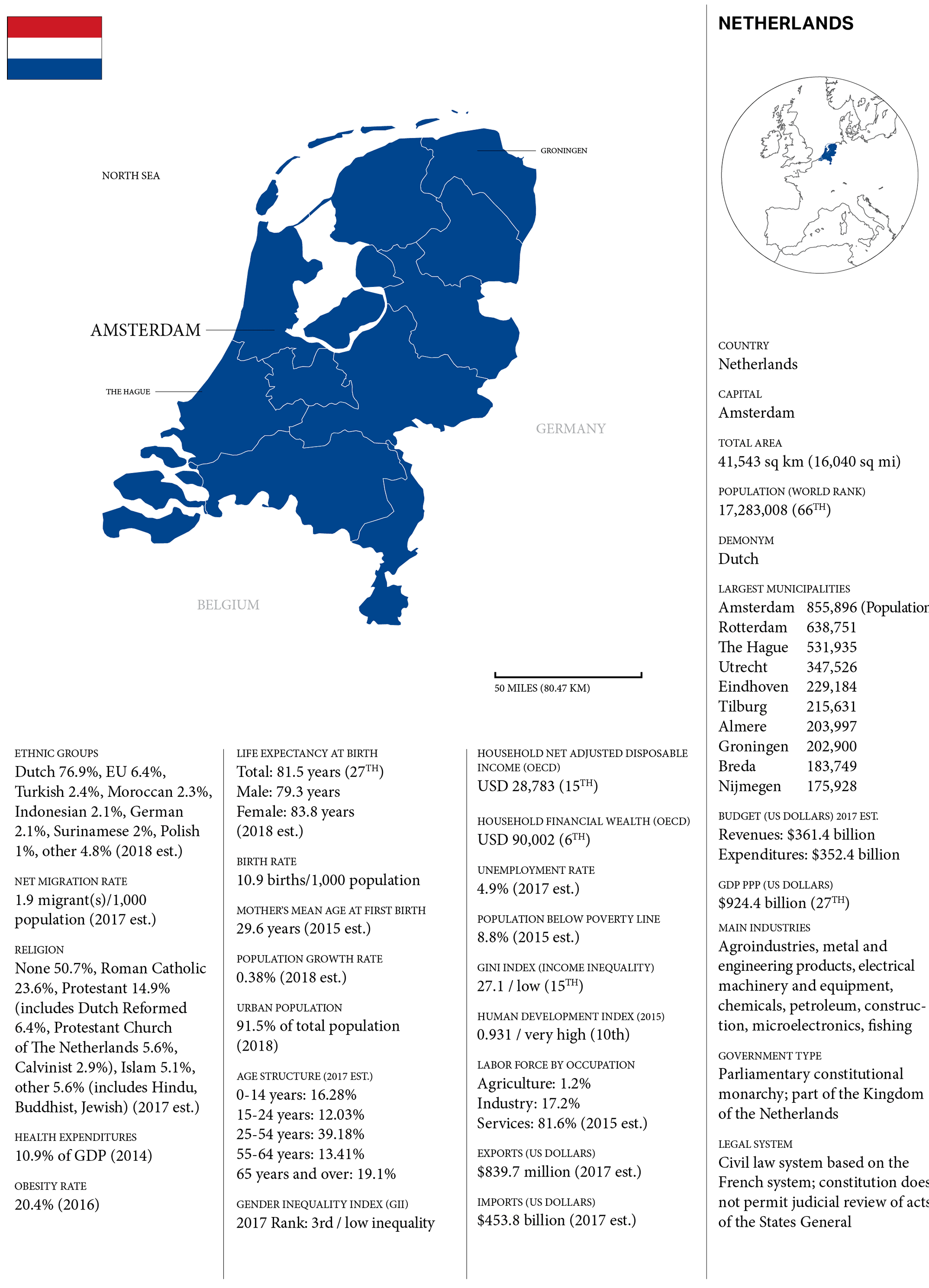

Like other Western European nations, the Netherlands is aging rapidly. It’s a small country, roughly twice the size of New Jersey, but home to 17 million people, making it one of the most densely populated countries in the world. Almost one fifth of the population is age 65 and older, a number that is anticipated to grow to 55 percent by 2050. As is the case in most places, increased life expectancy and low birth rate are at the root of the demographic upheaval. This is compounded by the graying of the country’s 2.4 million baby boomers, who are now entering the ranks of the 65-plus.

This age group is, for the most part, wealthy, healthy, and engaged, taking advantage of the robust welfare system that was built during the second half of the last century. The Netherlands is globally one of the most prodigious spenders on healthcare and long-term care, with a pension system ranked first in the world according to the Global Pension Index. The country’s economy is consistently listed in the top 20 worldwide, with a great percentage of its money going toward social welfare (health care spending accounted for nearly 13 percent of the GDP in 2016, according to the World Health Organization).

The Netherlands lays claim to a long history, stemming from deeply religious beliefs, of caring for everyone, especially the poor and vulnerable; this attitude remains embedded in the collective psyche. Most Dutch people find it unthinkable that money should be a determining factor in whether someone receives decent healthcare. In addition to their egalitarian nature, the Dutch are known for their open economy (a vestige of their merchant roots), tolerance, and liberal ideals. No topic is too difficult or taboo, including those related to aging, such as assisted suicide for older adults.

But, as is the case in many other countries, the cracks are starting to show. In the wake of the last economic recession, the government has been forced to look more closely at the long-term sustainability of the system. The anticipated glut of seniors who will need care, plus a general sense that the resources are running out, has necessitated reform. The older generation holds much of the country’s wealth, leaving the younger generation feeling stuck, sometimes without proper pension savings or comprehensive insurance, or unable to buy homes and start families.

Of course, the Dutch have a plan. A transition has been underway for some years now to veer away from the existing welfare state toward a “participation society,” in which individuals rely less on government handouts and more on themselves or family and community support. The 2015 long-term care reform act placed a greater emphasis on home-based care and aging in place, in lieu of more expensive residential nursing home care. This has understandably caused friction, as a generation brought up to believe that the government would care for them indefinitely is now forced to adjust their thinking.

“People, even with certain safety nets, will have to take more care for themselves and make some more decisions,” says Joris Slaets, Director of the Leyden Academy on Vitality and Ageing. “Hopefully, we can do that while retaining some of the things that make the Netherlands unique, like its solidarity.”

The Dutch character, and by approximation, its approach to its aging population, is inextricably linked to geography. On Google Earth, you can see the advantages of the Netherlands, perched on the upper northwest corner of the European continent — Germany to the east, Belgium to the south, and the North Sea on its northern and western coasts. In the seventeenth century, they ruled the seas from this choice location.

CURATED BY AARP INTERNATIONAL. DATA: CIA WORLD FACT BOOK / WORLD BANK / IMF / WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION / OECD BETTER LIFE INDEX / UN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS

The land is flat and mostly at or below sea level; it’s carved and crisscrossed with waterways of both the natural and manmade variety. Massive rivers and their tributaries wend their way in free-form lines across the map. Zooming in, the geometric angles and straight lines of a vast Mondrian-esque lattice of dykes and canals emerge alongside neat patchwork blocks of green farmland. This is a humanmade landscape, a feat of engineering that began hundreds of years ago, when the Dutch conquered the incoming sea — not only protecting themselves from the dangers of flooding, but reclaiming land from the water and making it usable. They are now the second largest exporter of agricultural products in the world, second only to the US.

Through the process of creating huge plots of land, or polders, the Dutch quickly learned that the easiest path to reaching their common goal (keeping their feet dry) was cooperation. The polder model, or the practice of consensus-building through discussion, is very much in use today — in the way government policies are created, decisions are made, and even in the way families interact, with children’s opinions being given almost equal weight to those of the adults.

The tradition has imbued the Dutch people with a straightforward propensity for sharing opinions (and willingness to hear everyone else’s opinions), along with an ability to reach across sectors. This, along with proven resourcefulness, practicality, and enthusiasm for facing challenges head on, make them well-equipped to find new solutions for the rising tide of seniors.

Japan, explored in depth in last year’s edition of The Journal, may take credit as the first nation to respond to the new demographic reality, but the Netherlands is working on its own set of answers. Though not yet a super-aged society, and not even the most-aged in Europe, this small, progressive country is already gaining attention for its expansive ideas on improving the aging experience. Only time will indicate whether the Dutch are once again able to control the fate of their nation, creating a working model for other countries facing a similar outcome.

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE SOURCE: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Online Demographic Profiles. Available from https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/DemographicProfiles/, Accessed on DECEMBER 2018.

POPULATION SOURCE: OECD (2019), Elderly population (indicator). doi: 10.1787/8d805ea1-en (Accessed on 03 January 2019). LIVING SITUATION SOURCE: Living Situation of Elderly People, Statistics Netherlands, The Hague/Heerlen/Bonaire, 2017.

Community Engagement

Seven years ago, Sofie Brouwer had something of an epiphany. Her aging, long-haired dachshund, Buffel, had developed back problems (a common ailment for the breed) and needed extra attention and care. Meanwhile, Brouwer’s neighbor Sonja Huisman, 69 years old at the time, had recently lost her own dog and was becoming withdrawn and isolated. Brouwer proposed putting the two together. During the day while Brouwer was at work, Buffel kept Sonja company, going on long walks through the neighborhood and generally having a lot of fun.

“All my neighbors saw Buffel more with Sonja than with me,” Brouwer jokes. Still, she was amazed at how well the arrangement worked out for everyone. It was a brilliant solution for Sonja, because it gave her purpose and companionship, as well as a reason to get out of the house. Brouwer gained a loving dog sitter for Buffel, but more importantly, she felt inspired to witness Sonja becoming an active member of the community again. She took the idea and started to expand it, realizing that that there were many more seniors who could benefit from such a setup. In 2011, she founded OOPOEH, a play on a Dutch word for grandma or grandpa. The acronym stands for Opa’s en Oma’s Passen Opeen Huisdier, or “grandpas and grandmas pet sitting.”

OOPOEH is just one example of an organization that is strengthening the bonds of community throughout the Netherlands. With the shift away from a welfare state to a participation society, older adults are growing more reliant on the infrastructure of social networks to provide not only care, but meaningful connections. OOPOEH matches dog owners with dog sitters aged 55 and up, facilitating relationships between neighbors who share a love for pets. For a modest monthly fee, dog owners find reliable care for their dogs. Seniors, or OOPOEHs, are able to spend time with a dog without the responsibility or burden of full-time ownership.

FROM LEFT: Sonja Huisman, OOPOEH founder Sofie Brouwer, and Brouwer’s dog Buffel; a senior with her canine charge; and an intergenerational friendship courtesy of OOPOEH.

“It’s just something that I thought creatively was a really nice way to fight and maybe even prevent loneliness,” Brouwer says. So far, the organization counts 3500 seniors and 3800 dog owners, and enrollment continues to grow. The oldest OOPOEH is 102 years old. A social impact study of the project found that 82 percent of the seniors felt happier after participating in OOPOEH, and 72 percent had more interaction with their neighbors.

Although loneliness is a growing issue, seniors 65 and up across the Netherlands are for the most part quite social, maintaining close ties to family members and other contacts and relying on the thriving system of community support apparent in Dutch culture. In 2016, a quarter of this age group report having daily contact with family, and one in five report having daily interactions with neighbors.

In some places, seniors who want more social interaction have taken the matter into their own hands, forming their own grassroots groups. In 2009, seven seniors in South Amsterdam formed what they called a Stadsdorp, or City Village — a group of seniors living in the same neighborhood banding together to create a support network, complete with special interest clubs and workshops on different topics. The success of this model inspired the creation of 24 other City Villages throughout Amsterdam.

Debora van de Water helped start one of those City Villages in 2013 — Stadsdorp Gracht en Straatjes, located in the heart of the city. Each of the group’s 170 members pays a yearly fee of €25 to belong. In turn, they are part of a community of neighbors who hang out together and look out for one another. According to van de Water, each of the City Villages are different, a reflection of the unique needs and interests of its residents. Her Stadsdorp has a tasting group for genever (traditional Dutch gin), a choir, a theater club, a coffee club, and a walking club, among many others.

“We have an expression in Dutch,” says van de Water. “You better have a good neighbor, rather than a friend who lives far away. So that’s what I think is really important.”

“We have an expression in Dutch,” says van de Water. “You better have a good neighbor, rather than a friend who lives far away. So that’s what I think is really important.” The idea behind City Villages thrives, in one form or another, all over the Netherlands. In the small towns and villages that dot the countryside, like the one where van de Water grew up, these kinds of social circles have always been the norm—from music and sports clubs, to church groups and neighborhood associations. In the anonymity of the big city, she and her neighbors have simply recreated the camaraderie and safety net of small town life. For seniors, whose social networks have naturally shrunk post-retirement, the City Village is a low-pressure way to stave off loneliness and make new friends.

According to van de Water, referring to the solid fabric of her neighborhood: “The best compliment is that, if the Stadsdorp stops existing — website’s down, we don’t do anything anymore — these new friendships never go away. They will always exist.”

Health and Vitality

Every Monday afternoon, Trees van Houts, 66, hops on a duofiets, an electric bicycle that accommodates two riders side by side. She pedals over to the home of her 93-year-old friend Marry Hagen to pick her up. The two will spend the next few hours biking around the town of Leiden, half an hour southwest of Amsterdam, and the surrounding areas, traveling 12 kilometers to the coast to see the beaches and dunes and breathe the fresh salt air.

Van Houts and Hagen have been “bike buddies” for only a year, but quickly formed a close bond. They met through the foundation Fietsmaatjes, which helps to bring the benefits of cycling to seniors and people with disabilities. Volunteers are paired with “guests” — those with limited mobility, vision, hearing, and cognition (primarily dementia), as well as those suffering from social isolation. With a duo bike outfitted with electric pedal-assistance, the biking pairs can take to the roads and trails, enjoying physical activity as well as social interaction.

It’s a testament to this bike-obsessed nation, that a woman well into her ninth decade still makes an effort to get out once a week on a bike, to feel the wind in her hair. And no wonder that the organization is growing so quickly. After just five years, Fietsmaatjes has 635 guests and 486 volunteers in locations across the country.

Trees van Houts, 66 (right) demonstrates the duofiets with Joke Strijk, 78.

BELOW: The organization Fietsmaatjes pairs volunteers with seniors and people with disabilities for weekly bike rides on a two-seat bicycle called a duofiets.

Throughout the Netherlands, seniors are living independently for a longer period of time, and they like being active. People between the ages of 65 and 75 cycle an average distance of 2.6 kilometers a day. The only group that cycles more on a daily basis are young people in their teens and early twenties. In 2016, nearly 16 percent of Dutch people aged 65 to 75 owned a membership at a fitness center, swimming pool, or other athletic facility, while more than 15 percent were members of a sports club. Those in that same age group are also the most likely to comply (at well over 77 percent) with the government’s Standard for Healthy Physical Activity.

It’s true that seniors here are afflicted with the same chronic disease as in other countries — heart disease, stroke, dementia, or lung cancer, for example. Obesity exists here, too, although the rate is lower than that in much of Europe.

But the Dutch perspective on active aging is certainly unique. The practicality that permeates so much of the culture also colors the approach to staying active. Exercise is not so much the act of going to a gym (although seniors do that), but something achieved through the machinations of everyday life. Errands and outings are largely done by bike, a continuation of lifelong habits for most seniors, whether they grew up in large cities or small towns. A glance down any Dutch street tells the story: Bike traffic is more plentiful than car traffic, with riders of all ages flying past on their way to school, work, and other destinations near and far from home.

As most people will tell you, bike riding starts in early childhood and stops only when no longer physically feasible. Van Houts describes how she started biking to school at just four years old. As a young woman, she raced competitively, but now, like many of her generation, cycles for practical reasons (to get from one place to another) and for recreation (to unwind and see the world in an unfiltered way). Volunteering for Fietsmaatjes was a natural step in her retirement to help bring the benefits of cycling to others.

When asked if she plans on biking until the very end of life, Van Houts leans forward, with a smile. “Let me tell you. My mother was 93 when she died,” she says, by way of answer. “I think she biked until five years before that.” It’s clear that she has every intention of doing the same.

Care Facilities and Dementia Care

The happy hour is going strong at 4:30 pm. The strains of an Elvis song reverberate loudly through the large, high-ceilinged room. People sit at tables scattered throughout the space, some with heads bobbing and toes tapping to the beat, others chatting with friends and sipping glasses of wine or beer. The feeling in the room is upbeat — from the enthusiastic bartender pouring drinks behind the tiki-themed bar, to the animated attendees. It could be a scene at a restaurant or club anywhere — but this happy hour is at a residential nursing home and all of the party-goers have dementia.

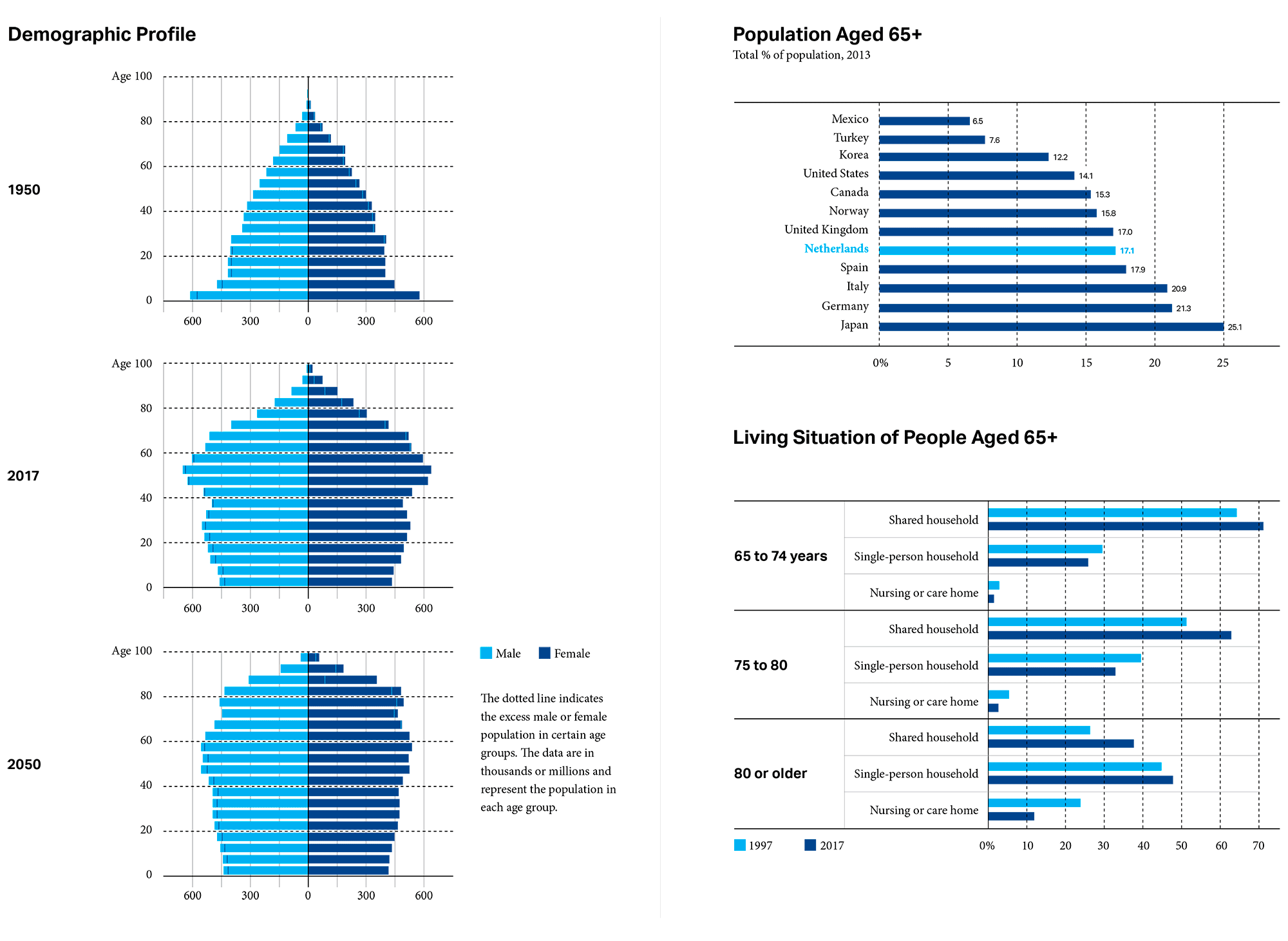

Henk Smit is the director of Reigershoeve, a facility on a swath of bucolic land in Heemskerk, roughly half an hour’s drive northwest of Amsterdam. He and daughter Dieneke Smit founded Reigershoeve five years ago after watching several family members struggle with dementia. They decided to create a “care farm,” so named for its gardens and farm animals, to provide an entirely different experience for people living with the disease.

During happy hour, residents who have no conflicts with medication are per- mitted to drink.

They, like others in the Netherlands, are rethinking long-term care. With the latest government reform in 2015 came an increased emphasis on keeping seniors independent for as long as possible, and on better tailoring care to meet the specific needs and desires of care recipients. For seniors who qualify for residential facilities, policies promote a greater focus on care that improves their quality of life. A variety of innovative solutions have been implemented nationwide, including an intergenerational model like Humanitas, in Deventer, which has incorporated university students as residents, and Hogeweyk, in Weesp, which built a “village” for seniors with dementia to provide more independence. To improve long-term care, all of these models reflect characteristic Dutch ingenuity and resourcefulness.

“Our vision is that people should live here as they were used to living before. That is why we don’t want to look like a hospital or like an institution. We want the people to feel at home here.”

At Reigershoeve, touches of home are everywhere in the buildings and grounds. Six to seven residents live in one of four group homes on the property. Inside, each of the homes has a communal living room and kitchen, warmly furnished with antiques and other personal items, as well as private rooms for each of the residents. “We call it small-scale dementia care,” says Henk Smit, referring to the Reigershoeve approach. “Our vision is that people should live here as they were used to living before. That is why we don’t want to look like a hospital or like an institution. We want the people to feel at home here.”

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: The buildings, both residential and administrative; a terrace outside one of the group homes; Henk Smit gives a tour of the grounds; a companion robot cat perches on a radio; tools are available in the workshop; the main communal kitchen.

Outside, residents can enjoy all the aspects of a Dutch farm: goats and donkeys roaming through grassy fields, chickens in a coop, raised vegetable garden beds, and a greenhouse with an abundance of plants and flowers. Activities like communal meals, movie nights, art classes, and happy hours also help to create a sense of community and normalcy. Adding to the familial atmosphere, the 45 staff members undertake any number of tasks, from cooking meals to doing laundry to caring for the residents — all of which, says Smit, encourages more interaction. In addition to the 27 residents, a dozen seniors with dementia also come to Reigershoeve for daytime care.

In typical Dutch fashion, Smit is quite direct about the challenges he encountered to fulfill his vision for Reigershoeve. From fighting initial protests of concerned neighbors, to convincing government inspectors to allow knives in the kitchens. He wanted to keep the knives as another aspect of home and normalcy that the residents crave. Smit encourages, as much as possible, independence. The facility has no gates or continuous monitoring. “We say well, when you’re at home, you can also walk around. Maybe it’s a risk, but we say, no risk, no life.”

Science and Innovation

The landscape along the A7 highway to Groningen.

BELOW: Richard Zwarts, a Lifelines participant and advisory board member, in his office.

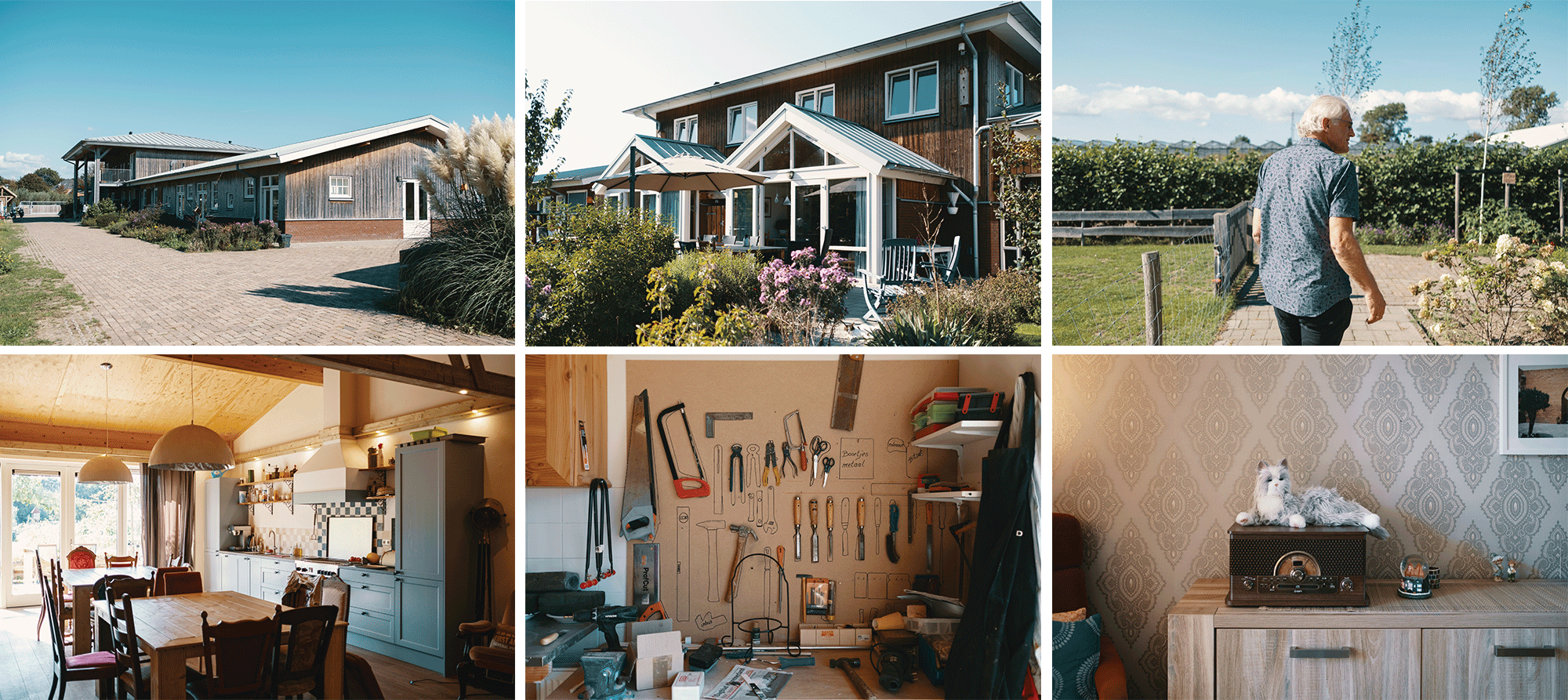

Although just a few hours by car from the cosmopolitan sprawl of Amsterdam, the northern part of the Netherlands feels vastly different, with long stretches of countryside extending as far as the eye can see. It seems an unlikely place for a hub of scientific research on aging, but here, in the northern city of Groningen, one of the largest multi-generational cohort studies of its kind is taking place. The goal for the three-decade study, called Lifelines, is to provide insights into how to grow older in a healthier way.

Richard Zwarts, a native of the area, is a Lifelines participant and member of the advisory board. He signed up in 2006, when the study was launched, after seeing a newspaper ad. At the time, he was only in his early 30s but was intrigued by the concept. “I am a guy who wants to share,” he says. “So, I think the idea is quite novel because when we share a lot, then we can learn, and other people can gain by that.” Every five years, he stops by for a checkup, various measurements, and tests of blood and urine.

This scientific approach to the aging challenge speaks to the Dutch embrace of research and innovation. The Netherlands competes in a class far beyond its size in terms of research productivity and scientific impact, with a robust system of world-class universities and research institutions. From 1996 to 2015, twice as many scientific articles were published per capita from the Netherlands as the OECD average.

The Lifelines study, with 167,000 participants across three generations, is ambitious even by Dutch standards. It is the largest biobank in the world, with a -80C storage facility, LifeStore, that bills itself as the coldest place in all of Europe. The data from the study has been used in 250 scientific publications, with several promising discoveries on the horizon. Dr. Bart Scheerder, of the Biobank Knowledge and Expertise center (BiKE) at the University Medical Center Groningen, which conducts the study, gives one example: “We have a large number of pre-diabetics in the cohort and we expect that in the future, major impact should be created on early detection and treatment of diabetes, using Lifelines data and samples.”

A globally-ranked university, the highest aging population in the country, and pockets of poverty and economic depression make the northern provinces ripe for such an endeavor. In addition, the Netherlands itself is an incubator for innovation, from strong government collaboration, to high education levels, to a cultural willingness to come together. The country now ranks as number two on the Global Innovation Index. “In the Netherlands, we discuss everything,” says Scheerder, who refers to that topic of polderen that keeps cropping up. “The nice thing is, we are also able to come to a shared decision. We bring all stakeholders together and come to a consensus.”

Nowhere is this consensus building more apparent than in another Groningen-based organization, HANNN, which stands for the Healthy Ageing Network of Northern Netherlands. Though Lifelines has become the flagship scientific aging initiative of the northern provinces, HANNN is doing something equally as innovative on a broader level, with goals that are bold and far-reaching.

The Lifelines Project, Groningen

Photos by Marieke Kijk in de Vegte for Lifelines

Every five years, measurements and samples are collected from participants in the Lifelines study. Part of the samples are used for direct biomarker analysis and the rest are catalogued and stored at -80C in the LifeStore, a large freezer facility. The aim of the biobank is to have data and samples ready for scientists from all over the world to use for research into healthy aging.

HANNN is a coalition of sorts, bringing together key thinkers and decision makers in different sectors to create an ecosystem for healthy aging. In short, the group wants to engineer the ideal environment to grow old — from food and exercise, to healthcare, to housing and city planning. Their programs run the gamut: working with fast food restaurants to introduce healthier menu options, with developers and architects to design age-friendly structures and parks, with schools and businesses to organize exercise programs.

The massive undertaking involves not only changing policies but changing mindsets. Daan Bultje, the director of HANNN, describes how he decided to chase such an ambitious goal, rather than attempting smaller, more incremental steps. “We have generations of people in certain areas of our region that grow up in poverty, but also in poor health,” he says. “Instead of saying well, let’s try to change a little bit about this, or a little bit about that, we need more fundamental change in how we approach health. That can’t be done by small steps. That must be done by big steps.”

Healthy Ageing Network Northern Netherlands

Photos courtesy of HANNN

The vision of HANNN is to remake the entire ecosystem of the Northern Netherlands, making it more conducive to aging well and helping to add healthy years to people’s lives. Through their many initiatives, the organization brings key players together to influence a variety of domains, such as food, housing, infrastructure, exercise, and healthcare organization.

Luckily, in the Netherlands, big steps seem more possible. With minimal rules and legislation and an openness to new methods and approaches, it stands to reason that the Dutch would lend their critical thinking to aging.

“We as a society need to change things, and not only in healthcare but also in prevention, making sure that we grow old as healthy as possible,” says Bultje. Both HANNN and the Lifelines study are at ground zero of efforts to conquer the changing demographics of their region.

Technology

Elie Rusthoven focuses intently on his laptop screen, where he is monitoring an older man named Hans from miles away. “I have a patient’s live data in the system,” he explains, indicating the digital interface that describes the current movement and condition of a man who lives alone — not down the hall from a nursing station. “I’m 1,000 percent convinced that, if this person didn’t have the system, caregivers would have already admitted this person into a nursing home.”

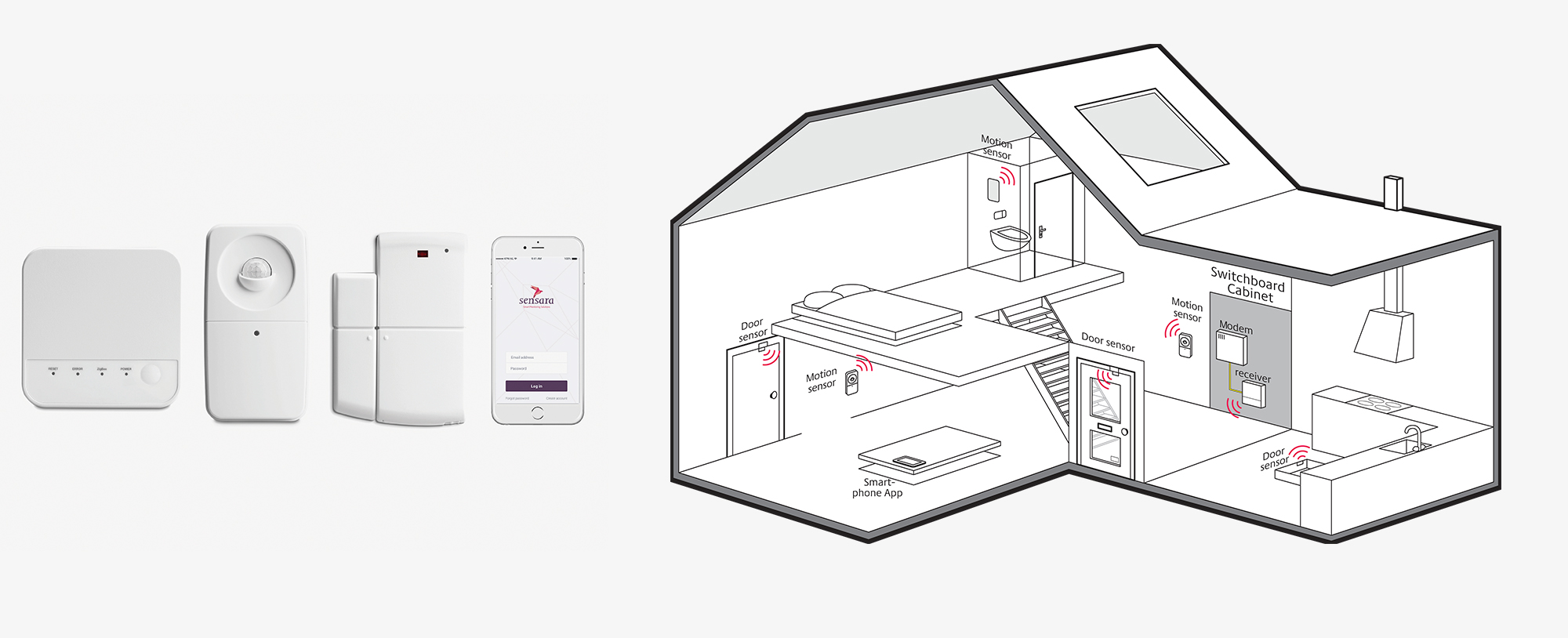

Rusthoven is Senior Project Leader of e-Health and Innovation at Cordaan, the largest care organization in the Netherlands with locations throughout Amsterdam and the surrounding areas. He is demonstrating the group’s latest — and from the sound of it, most promising — foray into lifestyle monitoring. The system involves collecting data from smart sensors placed unobtrusively around a person’s house, giving caregivers a way to monitor from a distance and allowing seniors to remain independent longer. Cordaan has partnered with Sensara, the Rotterdam-based company behind this sensor technology, to conduct a pilot program with 150 patients.

The Netherlands is a prime location for partnerships like this, and for using technology in new ways to improve the lives of seniors. The country has some of Europe’s most digital-savvy seniors, plus highest level of home internet access and high-speed broadband connectivity in the EU. Information and communication technology (ICT) has long been a focus for the government as part of an e-Health initiative that promotes increased health monitoring and better access to online medical data.

Receiver, motion sensor, door sensor, and mobile app by Sensara; a diagram of how the sensors are used in a patient’s home.

The research behind Sensara, begun in 2001, was ahead of its time in recognizing the coming onslaught of seniors and their distinct needs. The company’s patented learning technology relies on an algorithm that learns patterns in patients’ movements and habits, alerting caregivers when something deviates from the usual. Rusthoven provides an example by referring again to his patient: Hans was getting up 10 to 20 times a night to go to the bathroom. Because of Sensara, caregivers suspected, found, and treated a serious bladder problem. “We really believe this is the future of healthcare, incorporating continuous data to care for the elderly,” he says.

Though the word technology conjures images of futuristic monitoring devices or flashy robots, this particular tech is quite simple on the caregiver’s end. A dashboard signals red, green, or orange — an at-a-glance way to know if the person is all right. There are no cameras, microphones, or wearable devices, which some older people resist using — only simple wireless motion sensors. The entire process is meant to be easy and intuitive for both patient and caregiver.

Elie Rusthoven, project lead for Cordaan’s eHealth initiatives; nurse Getty Quarshie in the stroke rehabilitation unit.

Paul Ruijgt, business development director for Sensara, relays some feedback from a grateful woman who says Sensara is an “extra caregiver” for her mother. Within that testimonial is the crux of how the company strives to make itself as effective as possible, by marrying elements seemingly at odds with each other: caregiving (a deeply personal, human act) and machines. “The winning combination is personal attention and technology working together,” says Ruijgt.

For Cordaan, that outlook is key to creating a utilitarian tool. The Sensara system is not the first they’ve tested, but the most streamlined and user-friendly. The result comes from a very Dutch approach — implementing technology in a forward thinking, yet inherently practical way. “Technology is only relevant when adopted by the users,” reminds Ruijgt. That means using their inventions not just for the sake of showcasing technological wizardry, but in the smartest ways possible to make the most lasting impact.

Workforce Participation

André Weda, 61, lifts the piece of gold leaf with a paint brush and with several precise moves and a flick of the wrist, applies the fluttering, tissue-thin square to the curves of the wooden picture frame. His intern, Claudia Potgieter, 52, looks on in rapt attention. This process of gilding, or applying a high-end golden finish, is one of the most painstaking and difficult of the frame-making craft.

“I have to teach her,” Weda says, indicating Potgieter. “With gilding, you can read about it in a book, but by doing it, it’s something different.”

After 30 years in the business, Weda is an accomplished frame maker, applying his expert touch and artist’s eye to all the frames he creates. His shop, which he has run for two decades, and his distinct style is known among people in the surrounding town of Castricum, as well as in Amsterdam and abroad.

Weda teaches apprentice Claudia Potgieter the painstaking craft of gilding.

BELOW: Potgieter at work in the frame shop where she will study for the next year and a half.

Potgieter has been shadowing Weda for six weeks, coming to his store several times a week to learn every aspect of the craft — from assembling and painting, to working with customers and running a business. After losing her long-time job at a garage door manufacturing company, she was eager for the opportunity to start over in a field that interests her. By the time her internship is complete (a year and a half from now), Potgieter will theoretically be able to launch her own venture. “That’s the dream!” she declares.

This apprenticeship was made possible through a partnership between the government and AmbachtNederland, an organization that seeks to support small-scale crafts enterprises. “Ambacht” in Dutch means “craft.” With a grant of €2 million from the government, their program, Ambachtsacademie, was created to connect older jobseekers to job opportunities in various crafts industries. The two-year training programs will eventually help 200 unemployed people aged 50-plus learn and pursue careers in skilled trades such as bicycle repair, ceramics, wood working, cabinetry, and upholstery. Projections indicate that some 450,000 new craftsmen will be needed in the Netherlands through 2025. This solution, pairing senior interns with skilled artisans, is a win for everyone—giving seniors a chance to follow their passions while preserving certain crafts that might otherwise disappear.

“It’s for our culture,” explains Mascha Scholten, Marketing and Communications Director for AmbachtNederland. “It’s so important that [experts] can give their knowledge and their experience to another person. That’s why we are doing this.”

All this is an offshoot of a greater government effort to strengthen job placement assistance for older jobseekers, particularly those who have been unemployed for more than one year. With a well-funded plan called Action Plan 50+ Works, the government rolled out a number of programs, including Ambachtsacademie, designed to encourage the training, hiring, and retention of older workers.

In recent years, the percentage of Dutch seniors (age 65 and above) active in the labor force has increased, up to 7.7 percent in 2017. This is higher than the levels in most EU countries, in part attributed to the retirement and pension reforms that have been ongoing in the Netherlands since the early 2000s. The latest reform will raise the age for basic state pension eligibility from 65 to 67 starting in 2021, after which it will be linked to life expectancy. The end result is a change in attitudes towards early retirement and greater societal acceptance to working later in life. In a 2016 study by the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), 90 percent of respondents stated their openness to the idea of working beyond the retirement age.

“I have to teach her,” Weda says, indicating Potgieter. “With gilding, you can read about it in a book, but by doing it, it’s something different.”

In the back of the frame shop, Weda continues with his gilding lesson. He begins gently painting over the gold leaf with a finishing powder, explaining how to give the gold a perfect aged patina. Potgieter listens carefully.

“It’s the only way. It’s the only way to learn,” says Scholten, as she observes this interaction between teacher and student. “When she is ready, she will have her own style as well. That’s what makes it so beautiful.”

The picturesque canals of Amsterdam are lined with tall, leafy elms and the occasional weeping willow, with long tendrils trailing lazily into the water like a scene from a luminous, pastoral painting from the Dutch Golden Age. Boats of all sizes drift through the web of waterways, from massive enclosed tourist vessels to tiny motorboats filled with beer-drinking urban dwellers. Cyclists fill the streets and bike lanes, crossing the narrow stone bridges and weaving their way through the semi-circular arcs of the city.

Barbara Ederveen-Winkler’s apartment is just steps from a canal, in a quiet, residential neighborhood near the zoo. The inside is bright, with white walls and large, west-facing windows that, as is customary in Dutch culture, are left uncovered most of the time.

There’s a Dutch proverb that she mentions, geen zorgen voor de dag van morgen, which essentially translates to, “Don’t worry for what tomorrow may bring.”

She settles into the hospital bed that was temporarily placed in her living room after her skiing accident. Her bed, wheelchair, hospital and home visits, and ongoing physical therapy sessions — even the cleaning woman who comes to her place — were all subsidized by the government. For the most part, Ederveen-Winkler counts herself as extremely lucky to grow old here. Despite the plentiful bureaucracy and paperwork, she now recognizes she can age with independence, dignity, and joy. “We are a healthy, wealthy country. So there is still enough for everybody and there is care — maybe a little difficult to get, but if you need it, you can get it.”

Barbara Ederveen-Winkler in her Amsterdam home.

She mentions a Dutch proverb, geen zorgen voor de dag van morgen, which essentially translates to, “Don’t worry for what tomorrow may bring.” The meaning, not to be mistaken for resignation, alludes to the pragmatism of people here. No sense in worrying because solutions eventually will come. There’s a sense of confidence in the ability of their country to figure out the answers. This is, after all, a nation that wrested its land from the clutches of the sea. With enough ingenuity, resourcefulness, and collaboration, the Dutch will find a way to counter the next incoming flood — the challenges of an aging society — and even turn problems into opportunities.

When asked if she worries about aging, Ederveen-Winkler doesn’t hesitate. “No,” she says emphatically. “I’m still young.” She is already looking toward the day when she can once again hop on her bike and ride wherever she wants. ◆