By Francesca Colombo

Head, Health Division

OECD

By Elina Suzuki

Policy Analyst, Health Division

OECD

Download PDF

In few areas have the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic been more revealing of preexisting structural weaknesses than in long-term care. Over the past three years, older people, as well as those who care for them, have been hit hard.This is true even in countries with comparatively strong health and social care systems, as is the case across most of the 38 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states. More than 90 percent of COVID-19 deaths have occurred among people over the age of 60 across 21 OECD countries.1 Two in five COVID-19 deaths were among people living in long-term care facilities.2 This tragedy should not have happened, and addressing the vulnerabilities of the long-term care sector is imperative.

Longstanding Weaknesses Exacerbated During the Pandemic

Population aging is one of the most important global trends shaping societies. Across OECD countries, the share of the population ages 80 and older is set to more than double to reach 9.8 percent by 2050, up from 4.6 percent today.3 That we live longer is something to welcome, but our health and long-term care systems will need to adapt. Even when accounting for the uncertainties about the extent to which the extra years of life will translate into healthy living, the need for care services will grow as a larger share of the population gets older. Yet our aged care systems are not keeping up with demand.

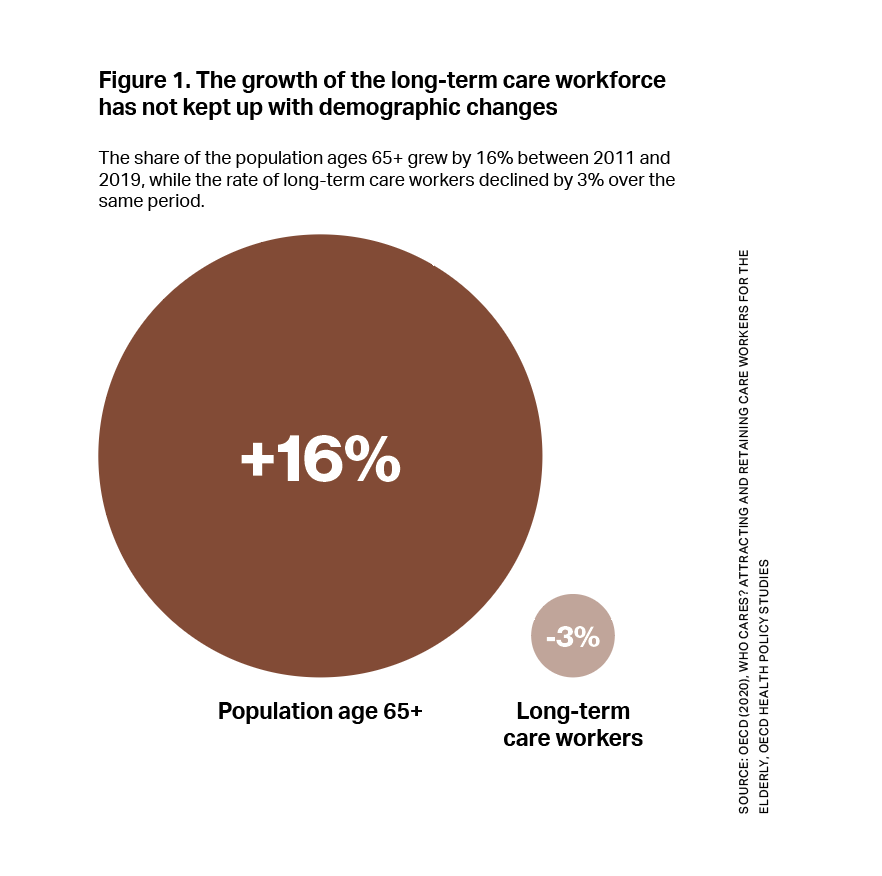

Source: OECD (2020), Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly, OECD Health Policy Studies

Consider the care workforce, for example. To keep up with population aging, the size of the long-term care (LTC) workforce would need to grow by 60 percent — or 13.5 million workers — by 2040 in OECD countries, on average.4 However, in more than half of OECD countries, the growth in the long-term care workforce is outpaced by population aging (fig. 1).

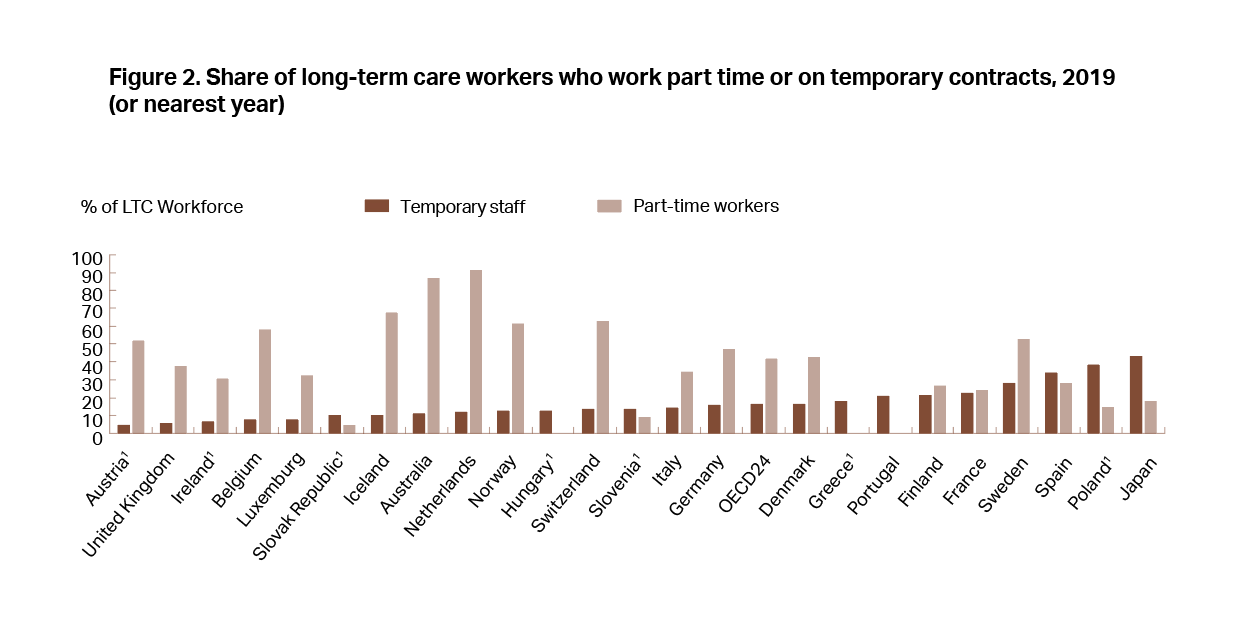

The complexity of the care older people require is also growing, and a mismatch in the skills of care workers has emerged. More than 7 in 10 long-term care workers are personal care workers with limited training; less than one-quarter of people working in the sector attended tertiary education.3 Low pay, insecure employment (e.g., part-time or temporary contracts), insufficient training, and a demanding work environment with multiple physical and mental health hazards all hamper recruitment and retention. In OECD countries, more than two-fifths of long-term care workers worked part-time in 2019 (fig. 2). Nearly one in five (17 percent) were on temporary contracts, thus increasing their chances of poor job security and lower access to social protection.3 Put another way, the current care workforce is not fit to meet the demand, and poor working conditions and mismatched or insufficient skills will only exacerbate the problem.

Note: 1. Data should be interpreted with caution because of small sample sizes, as defined by Eurostat based on EU member states guidelines. More information can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_labour_force_survey_–_data_and_publication#Publication_guidelines_and_thresholds

Source: EU-Labour Force Survey, OECD estimate based on national source for Australia, Survey on Long-term Care Workers for Japan.

Quality of care is another example. Even before the pandemic, some 40 percent of hospital admissions from long-term care were estimated to be avoidable, and over half of the harm in long-term care settings was preventable.5 Such avoidable care has a significant cost. In 2016, avoidable hospital admissions from long-term care were estimated to cost nearly $18 billion USD across 25 OECD countries, or more than 4 percent of the total amount spent on long-term care.5 Just one-third of OECD countries reported having policies in place to improve the coordination between the health and long-term care sectors.4

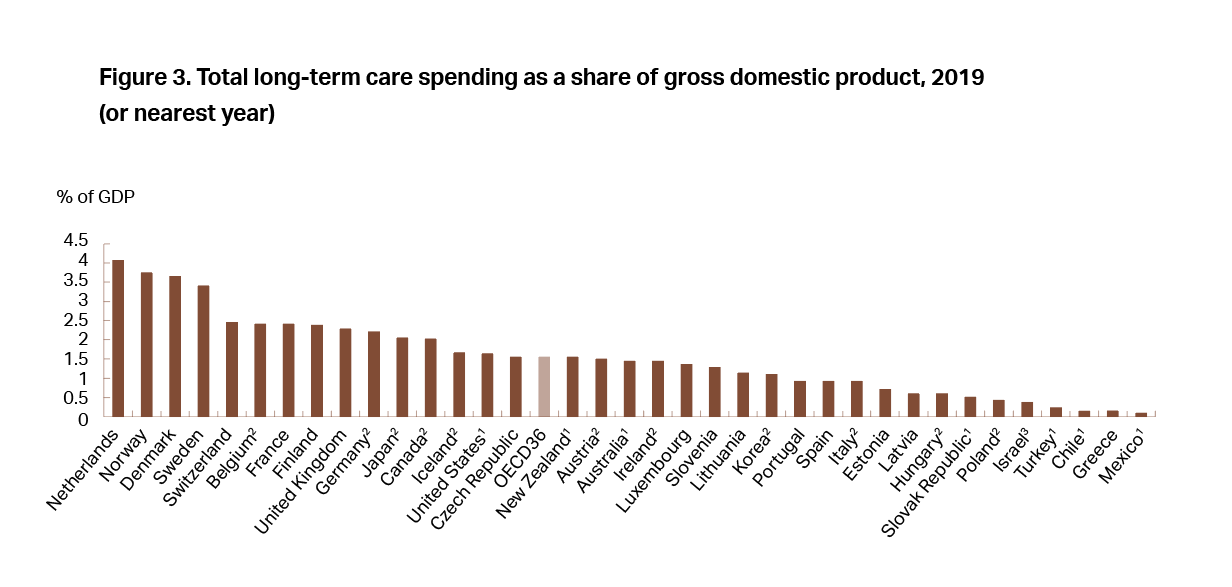

Many of the shortcomings that have plagued the sector were exacerbated by COVID-19. With only 1.5 percent of gross domestic product going to long-term care across OECD countries in 2019 (fig. 3), resources were not enough to face growing demand due to population aging, let alone the shock of the pandemic.3 Besides insufficient staffing and quality standards, supply shortages were widespread. Despite COVID-19 affecting older people more severely, the long-term care sector was initially not prioritized for containment measures, including the availability of personal protective equipment and testing. In many countries, long-term care was not included at all in pandemic preparedness plans.

1. Estimated by OECD Secretariat. 2. Countries not reporting spending for LTC (social). In many countries, this component is therefore missing from total LTC, but in some countries, it is partly included under LTC (health). 3. Country not reporting spending for LTC (health).

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2021; OECD (2020[6]), “Focus on spending on long-term care,” https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Spending-on-long-term-care-Brief-November-2020.pdf.

The Road Ahead

There is some good news. In response to the pandemic, many countries introduced policy changes and one-off initiatives designed to address the sector weaknesses. Close to 40 percent of OECD countries, for example, offered one-time bonuses to long-term care workers in recognition of their crucial role, and almost all countries reported efforts to improve recruitment and retention during the pandemic.1 Most countries also offered exceptional training programs to long-term care workers, notably on infection control and the use of personal protective equipment.

The adoption of many digital tools to help coordination across the health and long-term care sector has sped up. The proportion of adults ages 50 and older in European countries who reported having undergone a telephone or online medical consultation jumped from one in three in June–July 2020 to close to one in two by February–March 2021.7

Despite progress, further action is needed in at least three areas:

- First, access to long-term care needs to improve. Across 22 European OECD countries, close to 40 percent of people with difficulties in household activities or personal care reported unmet needs for help.3 In seven countries, the out-of-pocket costs of home care for severe care needs would be unaffordable even for a person earning a median income.8 Most countries lack information on how access to long-term care services aligns with need. Good data are also needed to evaluate whether money is spent effectively and efficiently.

- Second, quality standards must improve. Quality frameworks are often focused on inputs such as the buildings and on staff competency requirements. More and better indicators are needed in both care homes and home care, including the time staff spends with care recipients, how care recipients are treated, improvements in functioning and patient-reported outcomes, and improvements in care experiences. Making process- and outcome-oriented measures publicly available, such as publishing the results of inspections online, would improve transparency and accountability. In Sweden, municipalities must report quality indicators data in Open Comparisons available in a traffic-light format. In England, the Care Quality Commission conducts inspections and issues ratings for care providers.

- Third, measures to attract and retain workers need strengthening. Recruitment policies targeting people out of work, students, and those in sectors where labor demand is decreasing have proved effective in some countries, such as Japan. Promising avenues to reduce turnover in the sector include improving on-the-job training, raising wages, promoting a healthier work environment, and improving the organization through self-managed teams, as seen in the Netherlands, Australia, and Japan. Data on staffing, including hours worked, sickness absences, and other key metrics, also need to improve.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought to light longstanding critical problems in the long-term care sector. Without policy focus and action now, these will only grow in the years to come. Tackling them requires political will to make the changes needed, good metrics to help countries evaluate progress, and learning from benchmarking of good practices within and across countries.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or of its member countries.

See a list of OECD member countries at https://www.oecd.org/about/document/ratification-oecd-convention.htm.

––––––––––

1 Llena-Nozal, A., E. Rocard, and P. Sillitti (2022), “Providing long-term care: Options for a better workforce”, International Social Security Review.

2 OECD (2021), Rising from the COVID-19 crisis: Policy responses in the long-term care sector.

3 OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

4 OECD (2020), Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/92c0ef68-en.

5 de Bienassis, K., A. Llena-Nozal and N. Klazinga (2020), “The economics of patient safety Part III: Long-term care: Valuing safety for the long haul”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 121, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/be07475c-en.

6 OECD (2020), “Focus on spending on long-term care,” OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Spending-on-long-term-care-Brief-November-2020.pdf.

7 Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, http://eurofound.link/covid19data.

8 OECD (2020), Affordability of long-term care services, https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Affordability-of-long-term-care-services-among-older-people-in-the-OECD-and-the-EU.pdf.