Mexico is on the verge of a demographic sea change. Today, it remains a relatively young country with the second lowest percentage of people age 65 or older among countries covered in this study. However, the size of this group is projected to more than triple by 2050, largely driven by the country’s declining fertility rate. However, because older people remain a small share of the population today, the Mexican government has yet to prepare for the demographic shift and has not invested in the necessary infrastructure to support a healthy aging process.

Older Mexican adults have among the highest poverty and labor force-participation rates in the OECD, partly due to the country’s massive informal economy. Reducing labor informality has been a priority of President Peña Nieto’s administration. However, the government is not currently focused on implementing policies that would improve productive opportunity among the older-age labor force. Recognizing that aging is a looming issue, the government has begun to establish community-support infrastructure for older adults through its National Institute of Older Persons as well as long-term care infrastructure through the recently established National Institute of Geriatrics. However, the development of these initiatives is proceeding slowly, due to their low level of priority on the government’s policy agenda and a lack of resources afforded to the individual institutions.

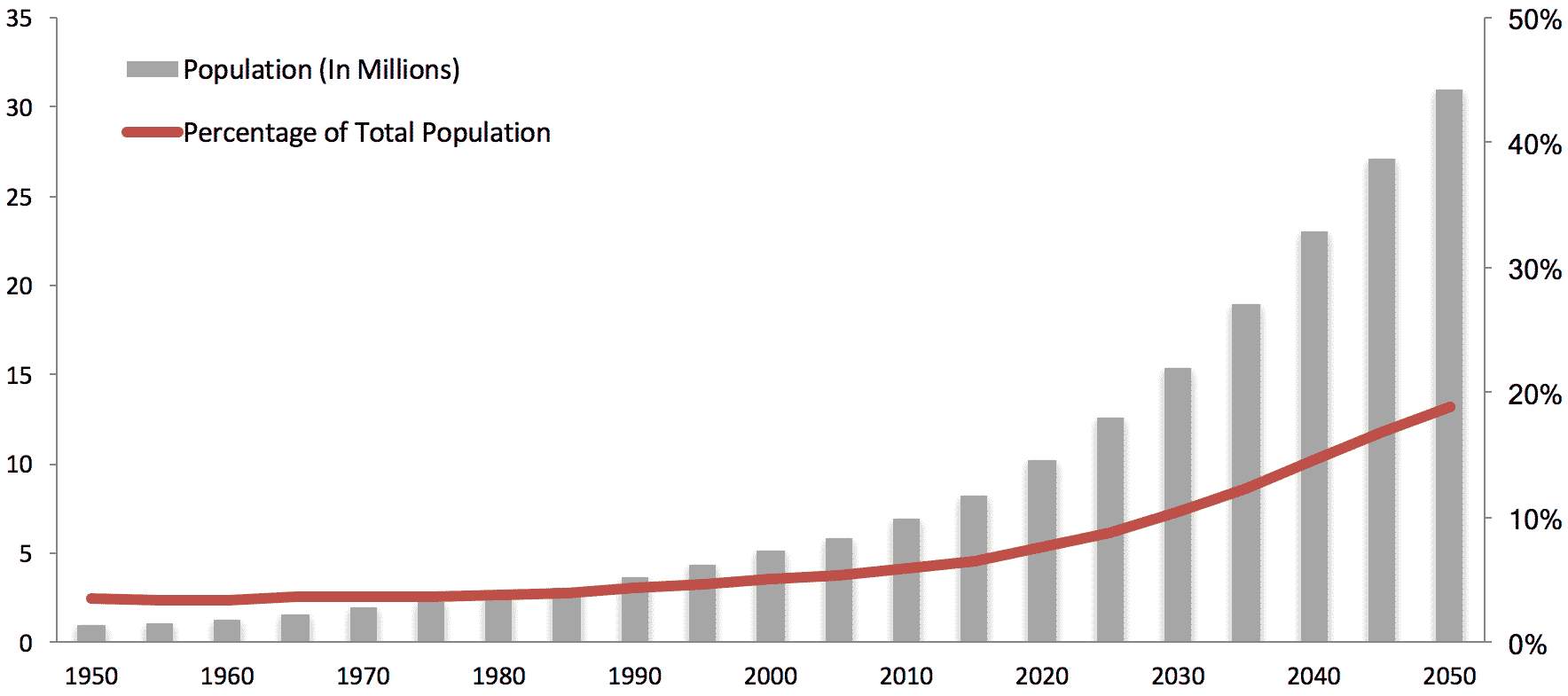

Number and Share of Population Age 65 or Older

Mexico’s population age 65 and older is projected to grow by 277 percent from 8.2 million in 2015 to over 30 million by 2050. This rate of growth can be compared with the growth rate of 194 percent for upper-middle-income countries and just 71 percent for high-income countries.

Source: UN Population Division

Community Social Infrastructure

While younger people’s migration to cities has led to changing family dynamics, the traditional multigenerational family structure has remained strong. Mexico still has the largest household size among all OECD countries – an average of nearly four members as of 2015. Outside of families, however, community-support infrastructure is minimal. The Mexican government has established an institution specifically dedicated to the aging population and has given it the responsibility of devising methods for implementing community-based support policies for older adults. While some programs to help older adults access transportation, food, and other basic services exist in urban areas, caregiving and support services for older adults are in short supply, and neither government nor non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have taken significant steps to provide community support for older adults nationwide.

As of 2012, more than 40 percent of older adults age 60 and older lived in extended households with members outside of their nuclear family, around five percentage points lower than in 2009.

National Institute for Older Persons (INAPAM)

The Mexican government opened the National Institute for Older Persons (INAPAM) in 2002 to ensure that support services were in place in accordance with the Older Persons’ Rights Law of 2002. INAPAM is charged with creating programs to assist older adults and prepare for population aging. While INAPAM is intended to serve older adults nationwide, the government has only provided it with enough resources and funding to provide services in Mexico City and other urban areas. One of INAPAM’s most popular services is a discount program available to all Mexicans age 60 and older, offering savings of between 10 and 50 percent on a number of goods and services. To obtain access to this discount service, one need only apply to receive the INAPAM card, which is accepted at a variety of service providers, including bus companies, taxi firms, local food and convenience stores, and other private businesses such as car service shops, clothing stores, and computer/tech shops. In total, there are over 15,000 establishments participating in this program in Mexico. INAPAM also offers psychological services for older adults who are hoping to avoid or cope with social exclusion, as well as career-placement services, cultural centers, and day residences.

Productive Opportunity

Older adults in Mexico work longer, on average, than their peers in most other OECD countries. However, this high labor force-participation rate is largely driven by the high poverty rate associated with the country’s large informal economy. The government has focused on alleviating poverty through a non-contributory pension scheme, with less focus on tapping the productive potential of its older population. Despite the desire to work, many older Mexicans face rampant ageism among employers, and local organizations report that this often begins at as early as age 35. Efforts to provide further education and training to help the older population gain employment remain scarce, and even moreso outside of large urban areas.

Informal and self-employed workers make up 60 percent of Mexico’s labor force, but this informal sector only accounts for 26 percent of the country’s GDP.

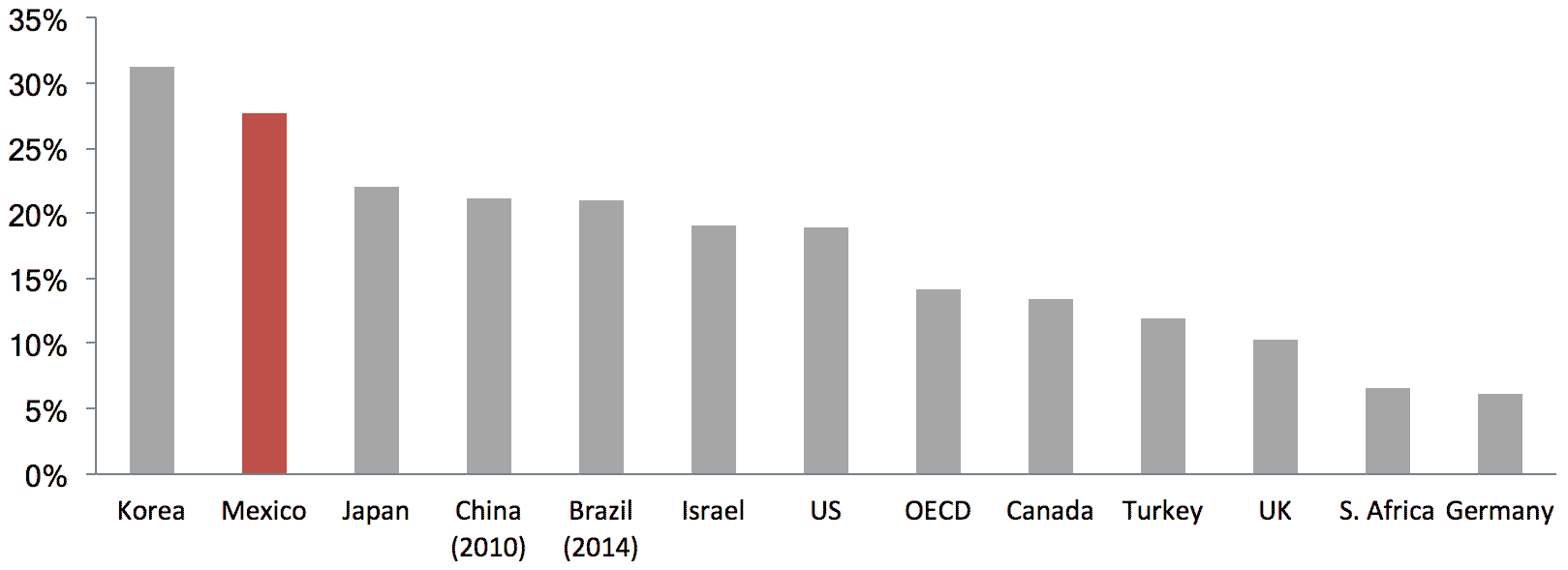

Labor Force Participation Age 65 or Older (As of 2015)

Mexico’s labor force participation rate among those age 65 and older was 27.7 percent as of 2015, nearly double the OECD average.

Source: OECD Statistics

University for Older Adults (Universidad de la Tercera Edad)

While policy support for training to help older adults gain employment is scarce in Mexico, there is one promising exception. Universidad de la Tercera Edad, a university exclusively for older adults, was established by the government of Mexico City in 2009. The university offers degrees in psychology and business administration, and its students of roughly 70 pesos to 335 pesos (approximately USD 3.75 to USD 18.00) per class, compared to over 18,000 pesos (approximately USD 1,000) per class at other universities in Mexico. The university also offers courses in other subjects, including computer science, law, English, history, and philosophy. It has produced more than 3,500 graduates.

Technological Engagement

Among OECD countries, Mexico has the lowest rate of Internet users. Basic forms of technology remain expensive, which is keenly felt by the older population, and negative perceptions persist about the value of the Internet. The federal government has implemented a National Digital Strategy to improve accessibility, and the Mexico City government is planning to establish an annual digital event to bring the experience of digital technologies to new users. NGOs are also working to provide technology training for members of marginalized communities, but like the government, they lack programs that specifically target older adults.

Only 3.1 percent of people age 65 and over in Mexico used a smart phone in 2014, and just 7.4 percent of adults ages 65 through 74 used the Internet, compared to about one-quarter and 42.5 percent of the overall population, respectively.

There are lots of fears regarding the possible negative outcomes of using technology, and particularly the Internet, some of which including fishing, scamming, junk mail, etc. This is a valid concern for older adults, since they are the most likely of all age groups to be ripped off or scammed through the Internet.”

– Aleph Molinari, Director of the Pro-Access Foundation

Digital Skilling Initiatives

Mexican NGOs are taking the leading role in increasing the level of access to modern technologies among older adults. Fundación Proacceso, or the Pro-Access Foundation, was founded in 2008 with the mission of reducing the digital divide and providing quali ty education to low-income areas in Mexico. As of 2015, the federal government and the government of Mexico State together provided the organization with 1.7 billion pesos (approximately USD 91 million). As a result, the organization has been able to expand rapidly. There are 70 digital-inclusion centers spread throughout Mexico. While about one million people have benefited from the digital skilling services that these centers provide, just 8 percent of these beneficiaries are above age 60. To attract older participants, the centers host Grandparents’ Day, when grandparents are encouraged to join their grandchildren and learn new skills together. The government has collaborated with The Pro-Access Foundation in attempts to replicate the model and achieve similar results on a larger scale. One such program, Puntos Mexico Conectado, aims to provide services similar to those provided by the Pro-Access Foundation on a larger scale by setting up one hub in the capital of every state in Mexico, to provide integrated services, including online learning and micro-entrepreneurship. Thirty-two sites have been in operation since 2015. While these efforts have the potential to go a long way toward normalizing inclusivity as technology continues to advance, Mexico still lacks programs that work specifically to engage with the older adult population and their relationship with technology.

Healthcare & Wellness

Mexico’s older population has a life expectancy and a healthspan that are above both the global and regional averages. However, unlike most OECD countries, they have actually fallen in recent years due to high levels of obesity and conditions stemming from poor diets and lack of access to quality nutrition resources. This has led to an increasing need for long -term care among the growing population of older adults, but the financial burden of care is higher than anywhere else in the OECD. The country has no formal system to provide long-term care and does not provide support for informal family caregivers.

Among Mexicans age 50 and older, 49.4 percent were found to be overweight, and 28.7 percent were found to be obese in 2015. The rates for the entire population were even higher – at about 70 percent and 32.8 percent, respectively – which bodes ill for future generations of older adults if action is not taken to reverse this trend.

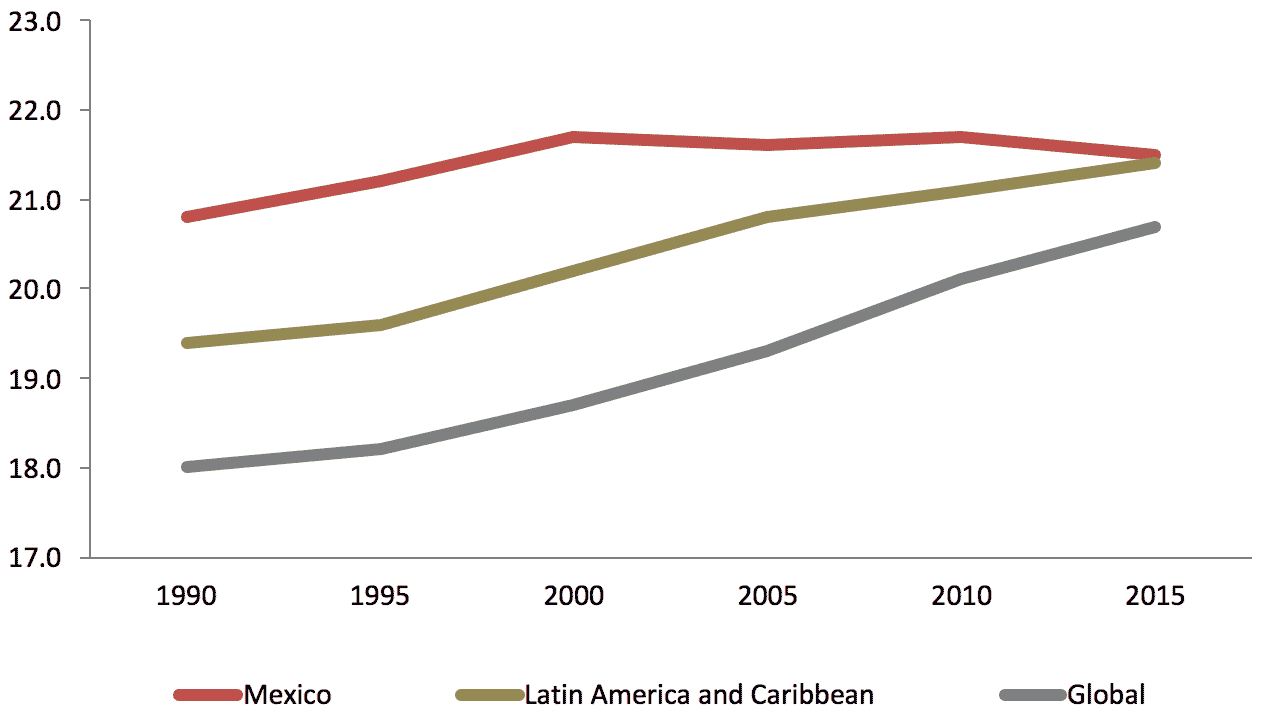

Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy at Ages 60-64 (in Years)

Both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy of older adults in Mexico have slightly declined – from 21.6 to 21.5 years and 16.9 to 16.8 years over the past decade.

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

Underdeveloped Long-Term Care (LTC) System and Early Efforts

As household structures shift away from the traditional multigenerational model, the need for a formal system for LTC continues to grow. This need is exacerbated by the high cost of private care options, which is typically between 18,000 and 30,000 pesos (approximately USD 1,000 and USD 1,700) per month, and by the lack of NGOs working to provide LTC services. The government has just begun to address this issue, giving INGER the lead in designing an effective infrastructure for LTC. INGER is focused primarily on research and education programs. It is also developing and providing training programs for the general population to assist with caring for older adults, as well as highly specialized geriatric training for hospital staff. The Institute also collaborates with international organizations like PAHO/WHO (Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization) to advocate for policy change through the Ministry of Health.