Japan became the world’s first “super-aged” society in 2006. Today, one in four Japanese citizens is 65 or older, and their share of the population will continue to grow, holding onto the country’s position as the world’s most aged society through 2050. The country stands out most because the population is not only aging but also shrinking. A falling birth rate and nearly zero net immigration have been the major contributors to this decline. At the forefront of aging societies, Japan is also a leader in preparing the country to accommodate a healthier and more productive and engaged older population.

The Japanese government has made employment opportunities for older adults a key component of its national strategy to revitalize the economy. The government has made significant efforts to assist job placement and extend the retirement age, contributing to the high level of older-age labor force participation, although enormous potential exists to further tap this productive opportunity. The government also recognizes the demographic shift as an incentive to boost productivity through innovations like robots, not only to close the labor force gap but also to address healthcare and nursing needs of the senior population.

Japan has implemented one of the most generous long-term care systems in the world in terms of coverage and benefits available to create an environment where seniors can thrive and live autonomously. The national government and local authorities have also tapped into their existing infrastructures and institutions to tackle social isolation. Civil society organizations and senior citizens’ clubs play crucial roles in enabling active aging and community-based engagement.

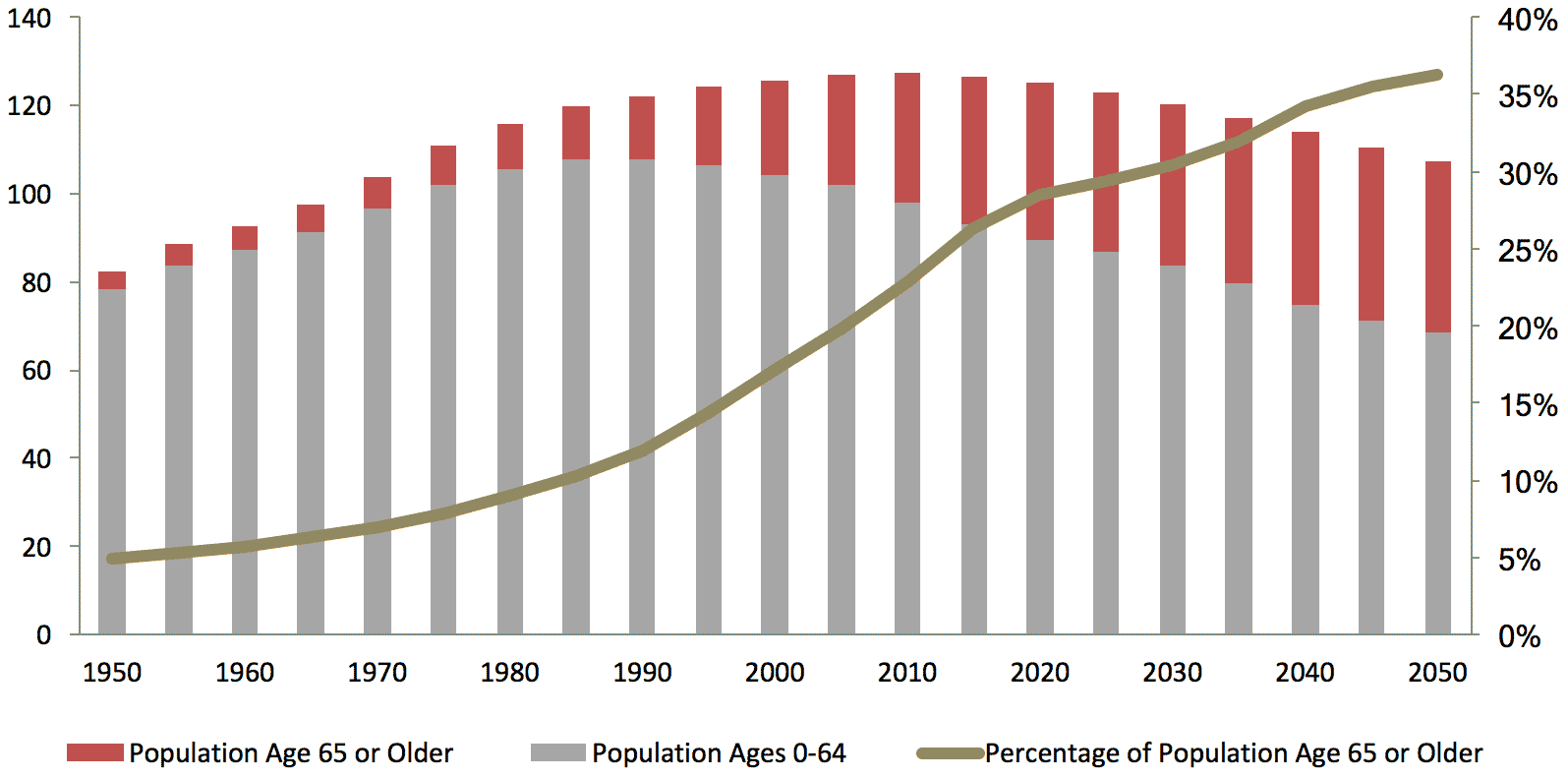

Japan Graph 1Population by Age Group (in Millions) and

Percentage of Population Age 65 or Older

Japan’s share of the population age 65 or older is projected to grow by one-third to 36 percent of the total population by 2050. From 2010 through 2015, Japan’s population shrank by almost one million people – the first time since the 1920s – and the decline is projected to continue.

Source: UN Population Division, OECD

Community Social Infrastructure

Rapid urbanization and demographic shifts over the last decade have laid the groundwork for a lonely and isolated life for many older people in Japan and provided the impetus to design a more age-friendly social infrastructure that supports the needs and wellness of seniors. Innovative solutions have been developed to utilize existing infrastructure to deliver services and to prevent social isolation. Housing and urban planning projects are incorporating new features to accommodate a healthy and independent older population. One area of weakness is in mobility. While Japan has made great strides, public transportation services in suburban areas and barrier-free facilities in older buildings are still lacking.

Today, 6.25 million people age 65 and older are living alone, an increase of more than 60 percent over the last decade. Nearly 45 percent of them are seriously concerned about dying alone, and this proportion is especially high – around 63 percent –for those who live alone and have a conversation with others only once or twice per month.

“Watchover Service”

One innovative solution that emerged to utilize existing infrastructure to prevent social isolation is the “watchover service.” It builds on the national network of Japan Post Group, a government-owned holding company, which operates 24,000 post offices around the country and has a workforce of 400,000. Japan Post first introduced support services for older people in 2013 on a trial basis in six prefectures – Hokkaido, Miyagi, Yamanashi, Ishikawa, Okayama, and Nagasaki – and expanded nationwide by the end of 2015. The initiative leverages the Group’s network of post offices and staff to monitor the health and well-being of older people and to report back to their family members. People can subscribe to one home visit per month for a monthly fee of approximately USD 20 and receive one check-in phone call for approximately USD 10. To improve service quality and efficiency, the initiative is incorporating new technology. In 2015, Japan Post collaborated with IBM and Apple to provide older subscribers with free iPads loaded with IBM-developed apps, which help to connect older people with services, healthcare, community, and their families. The apps enable older subscribers to schedule medical appointments, hire home-maintenance professionals, volunteer, and coordinate travel. During postal employees’ home visits, they also help subscribers address technical issues with the apps. This new service entered the pilot phase in the second half of 2015 and aims to reach four to five million seniors in Japan by 2020.

Productive Opportunity

Japan has the world’s most rapidly shrinking population ages 15 through 64, a trend that has elevated the importance of mobilizing the older workforce to boost economic growth and to meet public pension obligations. This economic imperative aligns with the interests of Japanese seniors, who have indicated a strong desire to remain active and employed. The government has adopted a variety of policy measures to increase workforce participation among older people, ranging from reforming the retirement system to assisting older people with job seeking. However, employers have yet to recognize fully the productive potential of the older population, thus far tending to hire older workers out of social or legal obligation. As a result, a mismatch persists between the skills and abilities of older job seekers and the nature of job positions available to them, leading to missed opportunity for the economy as a whole.

The average age that Japanese use to define “older people” is 73.7. More than 40 percent of people between ages 65 and 74 do not consider themselves “older people.” Nearly 70 percent of older Japanese wish to work beyond age 65, but only 20 percent are actually employed.

“While many older workers have extensive experience and expertise and are suitable for high-skill jobs, after they reach retirement age they are often replaced by younger workers and put in routine, low-skill jobs.”

– Toshio Obi, professor at Waseda University

The Silver Human Resource Center (SHRC)

First launched in 1974, the SHRC is dedicated to supporting older job seekers. Fully funded by the national and municipal governments, the centers provide community-based temporary and short-term job opportunities for older adults by matching job orders from private companies, organizations, and households with older job seekers. The SHRC has also operated a Senior Work Program since 2003, which helps to improve the employability of older adults by providing free skills training and job-interview preparation in cooperation with various associations of business owners and public institutions. As of March of 2015, there were 1,272 centers around the country with approximately 720,000 members. While the SHRC is rarely successful in helping older adults find jobs that are the same as they had before, beneficiaries gain opportunities to redeploy their skills and experience into new work. Small businesses in Japan, which are at a disadvantage compared to large companies in the competition for young talent, have proven particularly keen to recruit these older workers.

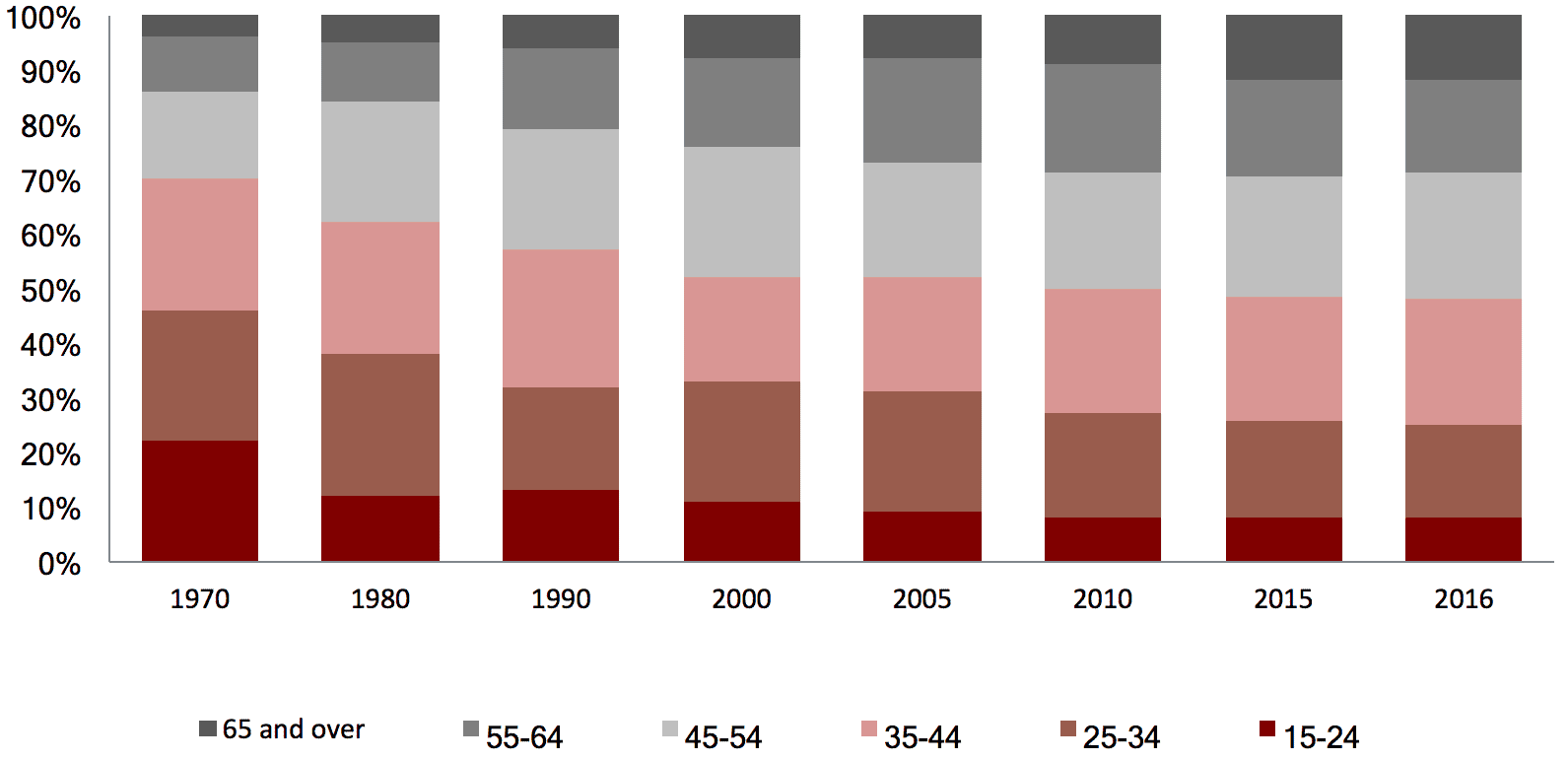

Percentage of the Labor Force by Age Group

The share of the traditionally defined working age (15 through 64) in the total population has decreased in Japan – from almost 70 percent in the early 1990s to 61 percent today. At the same time, older adults’ share of the labor force has doubled to 12 percent. As of 2015, 22 percent of Japanese age 65 or older were active in the labor market.

Source: Statistics Bureau Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, OECD

With over half of its population age 60 and over online, and the nation’s competitive edge in information and communications technology (ICT), Japan is better positioned than most countries to capitalize on new technologies for older consumers. The government has been seeking ICT-driven solutions in various aspects of older adults’ lifestyle, ranging from healthcare and social welfare to economic participation. The government and private sector are also seeking to secure a competitive advantage in the booming global older-age market, with a focus on developing robotics technologies to meet the needs of older people and caregivers.

Japan already has the largest number of patents in the robotics field, and in 2015 the government developed a five-year plan to support the robotics innovation, with one-third of the budget (JPY 5.3 billion or USD 47 million) dedicated to research and development in nursing and medical use.

The Otsuki project

Otsuki City, approximately 80 kilometers from Tokyo and located near Mt. Fuji, has 35 percent of the local population age 65 and older, many of whom are engaged in farming. In 2014, the local government, in collaboration with NTT DoCoMo and Waseda University, and funded by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, launched the Otsuki Project to promote e-Agriculture, e-Health, and e-Tourism. E-Agriculture connects the local farming industry with consumers residing in urban areas, like Tokyo, through digital technology. People residing in Tokyo can rent farming fields in Otsuki, and by using sensors, the Internet, and digital cameras, they can monitor the fields remotely and communicate with local farmers who are entrusted with daily maintenance. E-Health uses digital networks to enable local people, including seniors, to use a digital device to monitor their health status and send data to medical care providers. Pilot funding ended in 2016 as planned, but the local government has continued the program because of the tangible benefits achieved during the pilot phase.

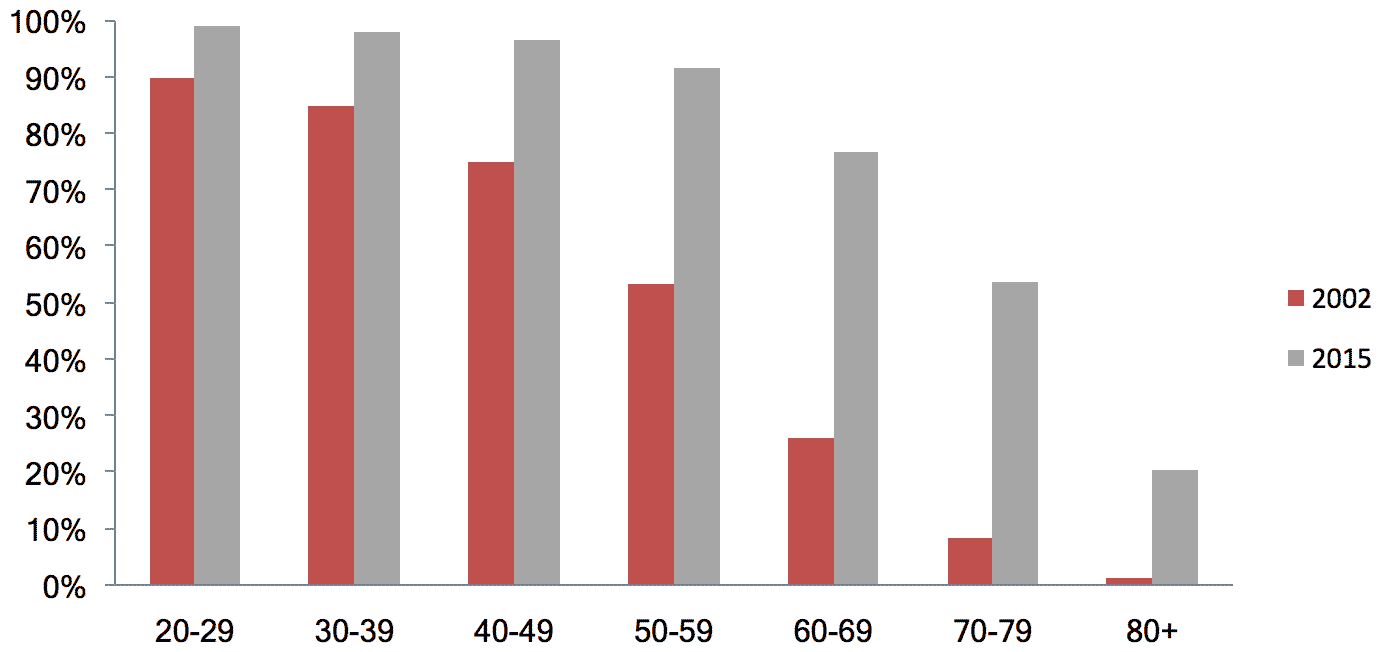

Internet Usage Rate by Age Group

Nearly three-quarters of those ages 65 through 74 are online, about 50 percent higher than the OECD average. From 2002 through 2015, the Internet-usage rate of people ages 60 through 69 almost tripled, and the rate for the age group 70 through 79 as of 2015 was more than six times as high as the 2002 level.

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

Healthcare & Wellness

Already the global leader in longevity, the share of people age 80 and older among the senior population will increase by more than one-third to 42 percent by 2050. Japan is one of the very few countries in the world to require long-term care insurance (LTCI). To keep up with the healthcare needs of the aging population and to ensure fiscal sustainability, the Japanese government has constantly adapted its LTCI program to enable older people to lead more independent lives and to support family caregivers. In particular, the government has increasingly focused on home- and community-based care and prevention programs.

Roughly 440,000 people are estimated to have left their jobs between 2007 and 2012 to care for their ill or incapacitated parents and other relatives, the majority of whom were in their 40s and 50s.

Supporting Formal and Informal Caregivers

To strengthen support for caregivers, the government amended the Child Care and Family Care Leave Act in 2016, which was first introduced in 1999, to introduce more flexibility into the program and to increase the benefit rate from 40 percent to 67 percent of salary. These changes were intended to strengthen the incentive for people to remain in the workforce. To meet the shortage of caregiving workers, the government also approved the creation of a new category of visa for foreign caregivers. As caregiving in general remains manual in nature, there has been limited growth in productivity of caregiving that could help cover the labor shortage. As a result, use of technology such as mechanical swings to carry patients as well as telecare services has been actively sought in recent years to meet demand.

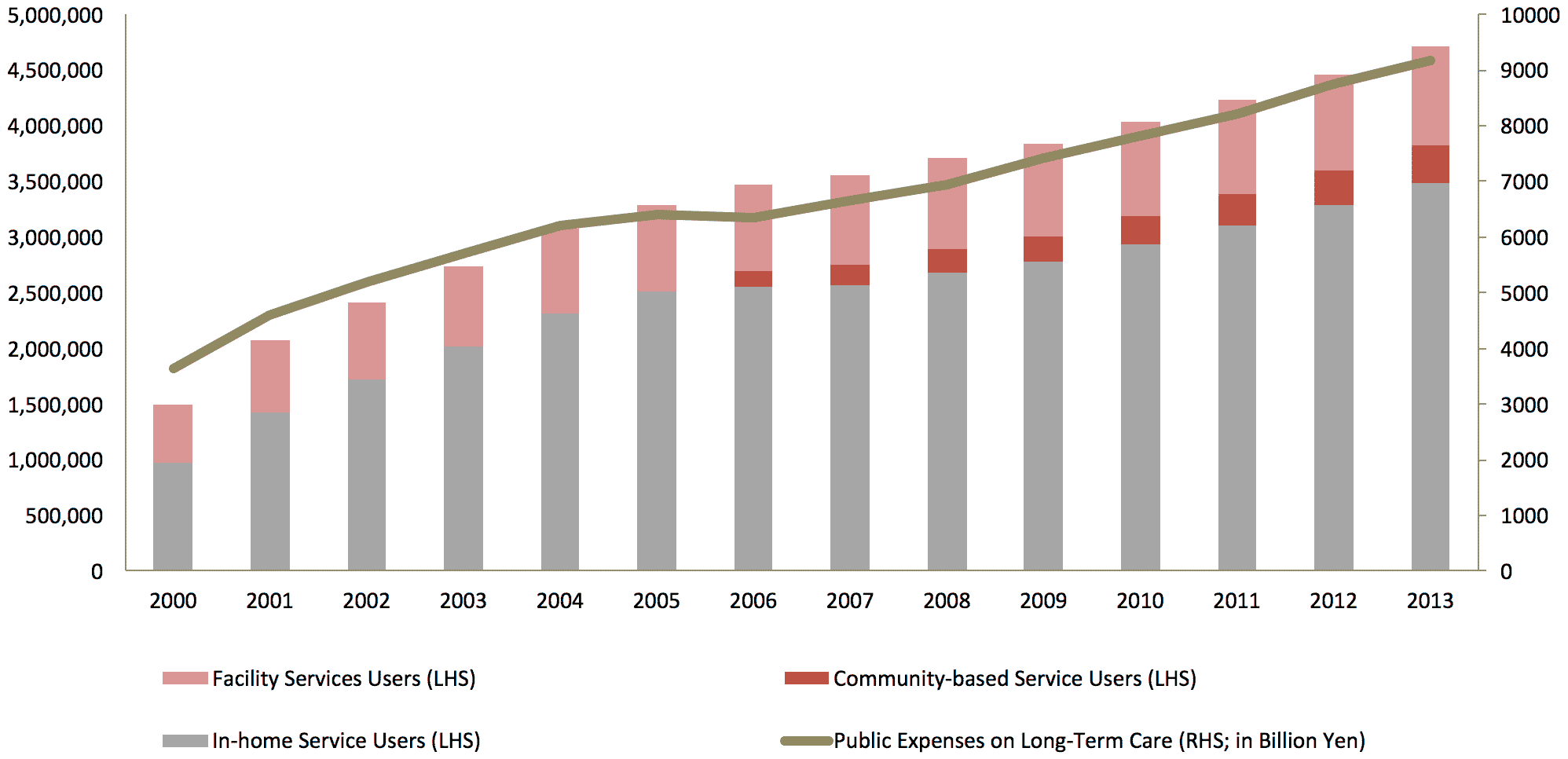

Number of Long-Term Care (LTC) Service Users and Expenditure

The government’s spending on LTC rose from 0.7 percent of GDP in 2000 to 2.1 percent as of 2015, and is projected to grow further to 4.4 percent by 2050. The government’s increased focus on home-and community-based care services has resulted in 50 percent growth in the number of users of these services, exceeding the growth of facility service users at 13 percent.

Source: Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare